Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: Foreign.

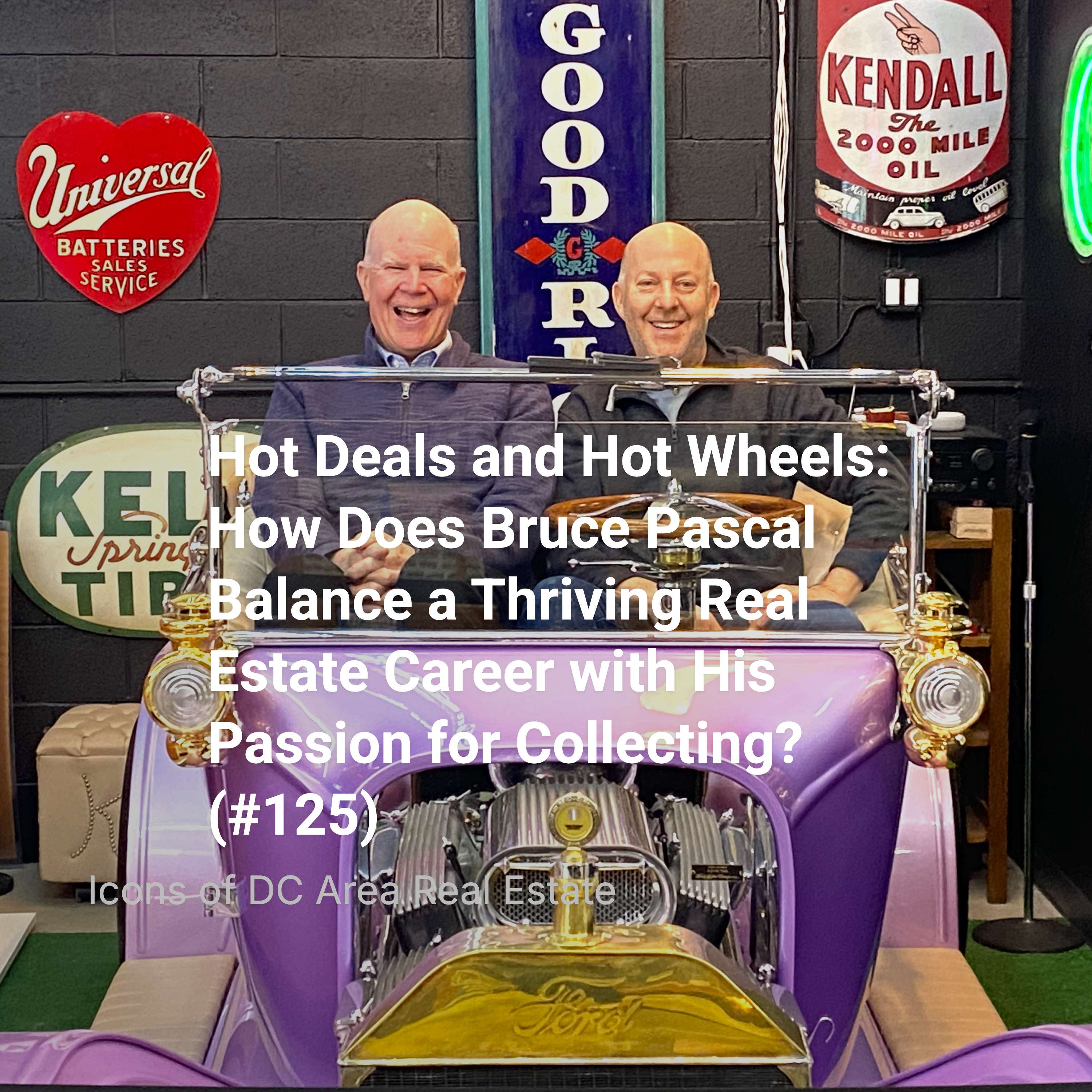

[00:00:09] Speaker B: Hi, I'm John Ko and welcome to icons of D.C. area real estate, a one on one interview show featuring the backgrounds, career trajectories and insights of the top luminaries in the Washington D.C. area Real estate market. The purpose of the show was to explore their journeys, how they got started, the pivotal moments that shaped their careers, and the lessons they've learned along the way. We also dive into their current work, industry trends, and some fascinating behind the scenes stories that bring unique perspective to our industry. Commercial Real Estate welcome to another episode of Icons of Deterior Real Estate.

I'm John Koh and today I'm joined by Matt Hard, Senior Managing Director at Trammell Crow Residential.

Matt would be the first to tell you that he has wood to chop before claiming icon status, but this conversation reveals something more enduring a seasoned perspective on judgment, stewardship and the long game of development.

We explore Matt's transition from a legal career where he learned to navigate the gray areas of risk to the principal side of the business.

He speaks candidly about the advantages and complications of starting out under his father, Bill Hard at elcor, who was also a previous podcast guest, and the internal pressure to earn the chair by mastering the unglamorous details of construction and execution.

We also dig into the current market moment.

Matt explains why his team is underwriting supply and demand fundamentals for the 2030 deliveries and why disciplined pursuit cost management has become essential to avoiding seven figure write offs.

The conversation doesn't stop at the professional Matt reflects on the personal resilience required to pivot careers during the height of COVID while simultaneously navigating serious family health challenges.

From his belief that being right is not the same thing as being effective to the quiet importance of reputation and trust in a cyclical business.

This is a conversation about what it really takes to lead over time.

Please enjoy my conversation with Matt Hart.

[00:02:42] Speaker A: So Matt Hard, welcome to icons of D.C. area real estate. Thank you for joining me today.

[00:02:48] Speaker C: Oh, good to be with you. And I should probably say from the top that the man need to put an asterisk on the title of this podcast with with your current guest here today, I think I have a a little more wood to chop in my career before I'm considered an icon. But flattered to be here. Thank you.

[00:03:04] Speaker A: Well, it's interesting if you know, last year I decided to go into the millennial slash Gen X generation a little bit more because I just felt it was I was ready to do that and I've interviewed you're going to be guest 145 for me. So I thought I'd try to transition a bit and I'd like a little fresher perspective and I was able to get that with a few of my guests last year. So I appreciate it.

So how do you define your mandate today at Travel Pro Residential company?

[00:03:39] Speaker C: Yeah, so, so our mandate today and generally speaking is, is focused, right, in that we, we focus on ground up, market rate, multifamily development, right. We don't do for sale, we don't do senior, we don't do tax.

So very focused in that it is market rate and it is development, but it is broad in the sense that, you know, we can play in the suburbs, do urban development, everything from, you know, three story walk up to urban high rise. So from that perspective it's, it's quite broad and at this moment in time, just where the market is, I'd say our mandate from our investment committee is to go out and tie up as many deals as we can, just being where we are in the cycle. And the fact that given the lead times in development, if we were to tie up a deal today, right, early 26, we're not getting to the ground until the end of 27 or early 28, which means we're not delivering until and at 29, 2030, which means we're not selling until 2031, you know, 2032. So when you look at it from that perspective, we think that's going to be a very good vintage just given the, the shut off in supply with the, with the drop and starts. And so now's the time for us to get active and, and start making some bets in our pursuits.

[00:04:54] Speaker A: Well, it's interesting, you know, there's a lot of variables that go into the equation when you make a bet. And one of them is in my experience in underwriting residential projects, is the return on cost analysis number, which usually is a benchmark for going forward. But you just said it takes almost two years to get in the ground.

So it's a really hard metric to say today it's 6%, but it might be 5 then, or it might be 7 then.

[00:05:28] Speaker C: Exactly.

[00:05:29] Speaker A: So you know, you're taking a lot of chances obviously because the pre development costs can be significant for these deals.

[00:05:36] Speaker C: Oh yeah, oh yeah. And to that first point, you know, now given the lead time item, we tend to think of things as, you know, untrended yield on cost, which is the state of things today. And then there's trended costs or yield on cost, which is the state of things, and stabilization.

But There's a third one which is because of the pre, pre closing period, which can be up to two years.

We call that the untrended at closing. So we've got three numbers. There's the return today, there's a return when we close, and then there's a return actually when we stabilize.

And when you look at it that way, your assumptions at this moment in time really come down to two assumptions in your model, which is the growth between now and closing and the cost escalation between now and closing. And so fortunately in this market where we're at is we're comfortable, you know, with a, with a goose egg for cost escalation just given the dynamics, you know, in the hard cost market. But we are comfortable, you know, modestly escalating the income side of things between now and closing. But if somebody doesn't believe that, it could be hard to get conviction today based on what the market is doing at this moment in time. Right. So that's, that's really the challenge.

[00:06:41] Speaker A: I'd like we can dive into this a little deeper because you know, there's so many variables and. But I want to keep going with my questions as I've written them. What decisions carry the most weight right now in your day to day work?

[00:06:55] Speaker C: So you actually kind of hit on it in your, in your previous observation.

My biggest kind of focus right now is the pursuit cost management. For us, especially since now we have the mandate to go out and tie up deals. But we, I mean we tcr, but also the royal we, our industry as a whole does have a bit of a hangover from 2022 when the market got disrupted and a lot of groups, including ourselves took off. Big write offs on deals that couldn't quite get to the closing line. And you figure for a typical deal, D.C. metro, I put Boston, this category, the coastal gateways. The cost of getting a deal to closing is exceptionally high. If you include deposits, it's between 3 and $5 million.

[00:07:40] Speaker A: Yep.

[00:07:42] Speaker C: So and let's just take that average, let's say it's 4 million and you've got three deals in the pipeline. Right. That's $12 million just for my division. And these are all deals that we're hoping we get to closing. You multiply that times 12 divisions in TCR. Then you multiply that across two companies because we have an industrial platform as well.

And it's very easy to picture a scenario if the bottom drops out and you go pencils down across the board, that write off risk is real. And so we are very, very mindful and very deliberate in how we escalate our commitment on these deals. And like you said, when we're, when we're making these bets we are being selective but it's the, it's the likelihood of success and getting fully capitalized that, that, that's, that's driving it. And just given the cost to get things done, we are not going to just h as much as we can throw it against the wall and see what sticks. Right.

[00:08:34] Speaker A: Well the other issue, and you always have these options. You tie up real estate, if you get it under control, you could just sit on it or you could sell it and sometimes make as much money or more than you could developing it and selling it as a, as a project.

[00:08:52] Speaker C: Which is one of those sellers are getting smart to that. I mean I'll tell you the last two deals that we've done, the thing that we've been most heavily negotiated is the obligation of us as the purchaser to advance the entitlement.

Right. And so, and we of course want the flexibility, of course, you know, either accelerate or slow down our spend in that two year pre closing period. From the seller's perspective they're saying hey, if you just sit on your hands for two years, don't advance the entitlement.

Yeah, sure, I'll get your deposit but otherwise I wasted two years and I could potentially miss a cycle opportunity cost.

[00:09:26] Speaker A: Yeah, sure, I get it.

[00:09:27] Speaker C: Right, right. But, but generally I, I agree.

[00:09:30] Speaker A: Well you just mentioned the, the key word cycle and you know, timing is everything in development success.

So if you go on the ground at the wrong time, I don't care how good a project it is, it's, it's gonna have a tough sled for the least first three to five years, stable stabilizing.

[00:09:51] Speaker C: And, and I definitely have some, some, some thoughts to share on that and list of questions but that is the most. One of the more eye opening things is my, you know, career has progressed over time is yes, you know, you can only control what you can control. So understanding what those things are is really important. And that's the exact otherwise we've had success in deals that nobody would have had on their bingo card and we've had, you know, kind of disappointing results for deals that we thought were a sure thing. And you know, one deal that we're getting ready to deliver this coming summer from the time we identified it, from the time we delivered my colleague and she's been working on this since day one. During that time when we signed the loi, she Started dating someone, got married, bought a house, had a baby, and we still haven't delivered this deal. And this is the surface, this is about a 15, 18 month construction period, but that's how long it took to get this and it didn't even.

So.

[00:10:47] Speaker A: Yeah, well, I can tell a 10 year story on that, but, but anyway, I'm not going to get into that.

[00:10:53] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:10:55] Speaker A: So what responsibilities do you feel beyond financial performance?

[00:11:00] Speaker C: So two things, principally, you know, the first being culture preservation. Here at tcr, we have a very, very strong culture. And of course, you know, in this business, being as relationship driven as it is, and the fact that TCR has been in business for 75 years. Right. We didn't get to where we are today with our brand by cutting corners and burning bridges along the way. So I would say our culture here is rooted in integrity. Right. Being honorable, doing the right thing.

Just because you can do something doesn't mean you should. Don't be pennywise and pound foolish. Don't fight for every last dollar. There's a lot of examples where we'll have something on the contract that we can enforce and we won't just because it doesn't feel right. And the culture here really starts from the top down.

So the way I'm treated by my investment committee, right. The way that I treat my counterparts, the way I treat my colleagues, we're just an environment where it's okay to make mistakes because, you know, the people in the C suite and our investment committee have been in our shoes before, so they know things go wrong.

[00:12:05] Speaker A: Right?

Yeah.

[00:12:07] Speaker C: As long as you're being transparent, as long as you're communicating issues, as long as you're not concerned about, hey, you know, our unit count dropped five units. I'm not going to get drawn and quartered by my investment committee. You know, publicly, you know, creates a, a very good environment where issues get escalated at the appropriate time. Because the only thing worse than having a problem is finding out you have a problem six months after the fact that somebody was scared to tell you.

[00:12:30] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:12:31] Speaker C: And then ultimately that kind of, you know, trickles outside of your organization. And how we treat our, our counterparties, our buyers, our sellers, and, you know, how we treat our consultants, right. We, we believe in, in repeat business. We believe in, you know, you know, rinse and repeating. And the way you do that is by having really, really good relationships. And so, you know, that, that is something that, you know, was one of the reasons why I, I joined and something that I take very seriously in our, in our hiring Decisions.

And I see that. The second thing, you know, that I focus on, and it's similar, but reputation management here, especially after the dislocation that we saw in this market, we want to be known or have a reputation amongst the brokerage community and the, you know, the sales community as a group that are straight shooters that do what they say, that perform. I mean, my goal at the end of a deal, right, is when we close to get a letter of reference from the seller that says TCR went under contract on this date. They said they were going to do A, B and C. They did A, B and C. And if I had more land, I would happily go under contract with them again. That's my goal.

[00:13:37] Speaker A: Sure. Yeah. There you go. So that's. Reputation is critical, obviously, in the business.

So I want to get into the Trammel Crow residential firm a little later and the gene a little bit about the genealogy of Trammel Crow because it's one of the most fascinating, if not the most fascinating aspects in the commercial real estate sector in all roads lead.

[00:13:59] Speaker C: Back to Dallas, as I like to say.

[00:14:01] Speaker A: Well, not just that. I mean, the company started in 1948.

Tramble Crow was the first brand in commercial real estate going back historically that still exists today.

So they were the old. They're really the oldest company in the business.

So it's, you know, and so you have a reputation to keep up. But you talk about brand management. There's no bigger brand than Trammel Crow Co. In my opinion, anyway. And we'll talk about that. So I want to now go a little bit into your background and your heritage.

So.

And of course, I interviewed your father, Bill, hard.

What did you absorb growing up by watching your dad operate in the real estate business?

[00:14:49] Speaker C: So from a. From a business perspective, I mean, honestly, not a whole lot. I mean, he, he was the kind of guy that left work at work and he was home every day for dinner, 6:30 on the dot, you know, came to all my sporting events with me and my. And my older sister, my younger brother.

And he didn't like dump his day on us as a family, kind of like I do with mine, right, where he just didn't really talk about it all that much.

[00:15:19] Speaker A: Now, he never took you to job sites or anything like that or talk to you about the business?

[00:15:23] Speaker C: I was gonna say, I do have very distinct memories of over the weekend, going to. I think it was an office building in Reston that was unfinished space.

Not sure why we were there, but we played hide and seek and tag, which, looking back, probably Wasn't the best idea to have young kids with rusty nails running around. But that was definitely a very fun core memory that I had. I knew generally he was in real estate, but, you know, it wasn't when he was at home. It wasn't just a big part of his identity. Right. Like, he was a dad first. And I just didn't. I didn't pick up on it, really, until middle school, where I started hearing this acronym over and over again, which was pto. Can I remember asking me, oh, what's. What's pto? And he said, oh, it's the. It's patent trademark Office. I said, oh, like, what? Why. Why are you talking about it? He goes, well, we're kind of doing the largest, you know, ground up gsa, build a suit in history. I said, okay, cool. I want to go, you know, play video games. That sounds fun. Good luck out there.

Right, right.

[00:16:22] Speaker A: So.

[00:16:23] Speaker C: So. So I would say, you know, I didn't start absorbing him, you know, from a business perspective, really, until after. After college and when I came into adulthood.

But for the most part, you know, he was not one to sit down and say, all right, son, you know, here's the. Here's the business I'm in and this works. And, you know, you should consider a career in real estate. Right. Like, that was.

[00:16:43] Speaker A: No, you are not Harlan Crow sitting at Trammel Crow seat.

[00:16:48] Speaker C: Yeah. And El was what was hardly a family business. Right.

So. Yeah.

[00:16:55] Speaker A: Yeah. Well, I had a chance to meet Bill's partners up in Philadelphia and all that at one point, because I don't know if Bill ever shared with you, but he was trying to sell USPTO at one point. And so I brought a few people to the table at that time.

[00:17:13] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:17:14] Speaker A: And we talked about it in the interview that I had with him. But anyway, what values did. Were. Were modeled in your household, not just from your dad, but from your mom.

[00:17:23] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah. I mean, it was, you know, obvious things like working hard and being kind. Those were all things that were modeled every day.

And my. My mom certainly was her percent of humor, and she had high expectations. Right. For us, but in a. In a kind way. She just had a high standard for us, which I think, you know, really imparted itself really at a. At a very, very young age. I mean, she, you know, I flashbacks us doing workbooks over the summer and, you know, was quietly encouraging us to, you know, just do a little bit more and do your best. Right. And so a lot of my work ethic, I, I think, comes from her. And she was really the rock that kind of held everything together in our house growing up.

But, but there was also things, more subtle things that only when I reflect on it do I really notice. But it was my dad's, you know, the modesty and kind of confidence.

[00:18:20] Speaker A: He's a humble guy.

[00:18:22] Speaker C: Yes, yes. And my mom is the same way. Right. And it was always, you know, be grateful, be kind.

Things could always be worse. Put things in perspective. Those were a lot of, you know, have gratitude. And I think you may have touched on this in my dad's. But obviously in the. When my mom passed away in 2020 after a four year struggle with breast cancer, you know, that whole time she was, she never complained once.

Right. She reminded all of us to be grateful. She would tell us, you know, don't, don't feel bad for me. I've had a wonderful life. I mean, that was the kind of person that she was, you know, and when I think of my dad, I think of. I think of the modesty and the quiet confidence that he had. And, and when I realized, you know, when we started working together that that translated, he was the same person at home as he was professionally speaking. And you don't know that you actually start to work with somebody. I mean, there's a chance he could be the kind of guy where he walks in the office and a switch goes off and all of a sudden he's a chest beating, you know, lunatic. Right. I suspected that wasn't the case, but I found that, you know, his approach and how he did things, it made him authentic, like, and somebody you want to be business with. And so that's something I try to. Try to emulate.

[00:19:33] Speaker A: I'll bet.

Yeah.

Did you, did you feel expectation or quiet, quiet guidance around your career?

[00:19:41] Speaker C: I think I felt neither of those things, to be honest. I mean, to my parents credit, quiet guidance in the sense that there was an expectation on, you know, doing well in school and being well rounded and participating in things outside of school.

[00:19:54] Speaker A: Be the best person you can be. Right, Right.

[00:19:56] Speaker C: So that was certainly an expectation. But as far as the crew and really major decisions like where to go to college, for example, they left that all up to me. And if anything, interesting, I was, I was kind of craving a little, you know, I wanted to be told kind of what to do. I mean, life's always a little bit easier if the path is laid out for you.

[00:20:16] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:20:17] Speaker C: I'm the kind of person, I can get a little overwhelmed if I have too many options. Right. You know, for anything for. For for big decisions. So there were times when I went back where I'm like, you know, mom, dad, can you just tell me where to go to college? Like, I can't make this decision. This is too hard.

And so they gave me the tools, they gave me the canvas, but the expectation was that I made the decisions on my own.

[00:20:39] Speaker A: Well, where did you feel you need. The need to define your own path in essence?

[00:20:45] Speaker C: Yeah. Well, I mean, in a way, it was kind of always the expectation. You know, with my dad, I didn't really know that real estate, or at least working with him was going to be an option until I was in my late 20s.

[00:20:58] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:20:59] Speaker C: So when I made the decision to. To. To move and come out of college, I moved out to California.

That was an opportunity to kind of, you know, spread my wings and experience a market in a life. You know, a little bit of distance from the core family.

[00:21:14] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:21:15] Speaker C: I was looking for distance, but, you know, kind of spread my wings, put some roots down, try something new.

And so that was. There was no light bulb moment where I was like, okay, I'm gonna go out and forge myself. My parents just always encouraged me, find a career that. That you enjoy and all work.

[00:21:30] Speaker A: Yeah. So you went to Georgetown.

[00:21:32] Speaker C: Yes.

[00:21:33] Speaker A: What was your focus there and why Georgetown?

[00:21:36] Speaker C: So I was. I was really drawn to Georgetown. I liked the liberal arts factor of it, and I like the fact that it was in a city and it was in a city without feeling like it was in a city.

[00:21:46] Speaker A: Right.

[00:21:46] Speaker C: Compared to some other urban schools.

I didn't pick to go there because it was close to home. I probably went home as much as I would have if I was out of market. But obviously the brand. I was drawn to the liberal arts nature of it, the Jesuit education.

And during school, I was very much a generalist. I was a political science and English major. I. And I took classes in all departments. Psychology, sociology.

[00:22:13] Speaker A: Right.

[00:22:14] Speaker C: You know, you name it. So when I graduated, you know, being a generalist is probably the most charitable adjective. Unfocused could probably be another one.

[00:22:23] Speaker A: There you go. Yeah, I get that.

[00:22:25] Speaker C: Yeah. And so I found myself, when I graduated, I had all. All sorts of interests across the board. Right. Every month I was on a different kind of career path. I was, at one point I was going to be a journalist, and then I was going to go work for the FBI, and then I was going to be a lawyer, and then I was going to try to, you know, figure out how to go up to Wall street, which Georgetown does tend to be a theater up to Wall street, there's a lot of opportunities for that.

[00:22:47] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:22:47] Speaker C: But I found when I was flying to those jobs, I was competing against people who have been focused on that thing.

Freshmen in there, they had a resume, so to speak. So I was, you know, kind of all over the place. But you know, through all that I, I look back and I had just had a very well rounded education, you know, learn how to learn, learn how to think type of education, but I can't do anything, practically speaking. Yeah, that.

[00:23:10] Speaker A: Did you look at McDonough at the time or not? Did you think about.

[00:23:14] Speaker C: No.

[00:23:15] Speaker A: You didn't think about the business school there?

[00:23:16] Speaker C: No, I didn't have parents telling me I should consider a practical degree. I mean.

[00:23:22] Speaker A: Have fun.

[00:23:24] Speaker C: It might be a good idea to take a finance or an accounting class.

[00:23:27] Speaker A: Yeah, right.

[00:23:28] Speaker C: I'm giving them a hard time. But, but, but no, I didn't, I was, I was happy kind of exploring the, the softer studies.

[00:23:36] Speaker A: But then you, you decided to redirect and get serious and go out west.

So why usc? Why not other schools? What, what did you look at?

[00:23:46] Speaker C: So I basically applied to every top 25 school in a major city and I got two of them. So that helped narrow it down.

[00:23:57] Speaker A: Was a focus on law or did you want the joint.

[00:24:00] Speaker C: Yeah, law, law and, and, and, and it's a bit of a cop out, but like many people do who graduate and you know, we're driven, we're type A, but don't necessarily have a focus and you know, don't really know what to do. And you're, you know, you're 22, 23, you got the anxiety. What does the rest of my life look like? And then you got the warm cozy blanket of spending three years learning a certain body of work that clearly translates into a long term career path. That's what drew me to the law. I mean, and there was always growing up, you know, you'd hear my mom would say, well, you know, you like to argue, Matt. So you'd be a great lawyer. Right?

I mean, I don't think that imprinted too much of me, but I knew that law was going to be a very flexible degree for me. I knew that it could turn into, you know, litigation. I knew it could turn into, you know, transactional work or something not involving law at all. Which of course is where, where I ended up. And USC specifically, I, I had been drawn to the entertainment industry, believe it or not, kind of as a young kid. Okay, as we were chat before this, I, I grew up as a swimmer and a Runner and maybe I was jealous of the, of the people that played ball sports but I have almost no sports knowledge like of mainstream sports. But what I don't have in that I make up for in like movie, tv, entertainment type trivia points. So I, I, I was always, I always love movies and love tv. So I thought if entering that, that business was ever going to be an option or something I was interested in pursuing. The best way to do that is to be at a place like USC in Los Angeles. Because if you're not in New York, Los Angeles, it's not going to happen. So actually when I was out there, spent a lot of time I did an internship at Sony Pictures, I did an internship at a talent side representation.

[00:25:43] Speaker A: That's cool.

[00:25:44] Speaker C: You know, studied a lot of ip so that for me was, was an option like and, and the emerging theme here is I was always hedging my bets.

Right. Which also ties into tacking on the mba, that hedge there.

[00:25:57] Speaker A: And at the time you take classes at the Lusk School there, the real estate program.

[00:26:01] Speaker C: No, this was, this was at Marshall, this is the Marshall School of Business.

So I didn't do the. Because they have an EMRIT program. Right.

Development. Right. This was the mba.

When I was making these decisions I was not focused on real estate and it was been as much by self preservation as it was by an interest in business school. Again, hedging my bets, not having that curriculum in undergrad.

My recruiting year in law school was the fall of 08, which as you can imagine was not a good time to be getting recruited law firms, especially because you talk about lead times. I mean you're basically interviewing for jobs two years before you would start full time because you're interviewing for the summer associateship the next that then hopefully turns into an offer for the summer after that after take the bar exam.

And so in the fall of 08, hiring basically shut down. Nobody was getting, I mean across my class. And so by tacking on the mba, it would only be one extra year of coursework. So I could do it in four years instead of five. But it also gave me another bite of the apple on the recruiting side of things. In the fall of 09, which is when I actually was able to get and secure an offer for a summer associateship. So two birds, one stone, right? Hedge my bets and get another bite at the apple.

[00:27:17] Speaker A: On the, on the looking back, did you learn a lot? I mean was that a good combination of things to help you understand both the business and legal side of things?

[00:27:26] Speaker C: Yes, yes. For sure, for sure.

[00:27:30] Speaker A: And, but you still, even with the mba, you just said, I'm going to go law, I'm going to give that a shot, see what happens then.

[00:27:36] Speaker C: Yeah, well, at that point, being starting out of the law firm, number one, I had some, I had some student debt. And it was just the starker reality that starting salaries were higher for, you know, a post mba. I'm sorry, higher for a JD versus a post mba. But, but the practical reality was I wasn't getting job offers and things that weren't. The, the law path was the one at that point I was most qualified for because I only, I didn't have so much, a lot of work experience, so to speak, before I graduated.

[00:28:05] Speaker A: Right.

[00:28:05] Speaker C: Again, it was, you know, the people who were in the NBA were a little older, they had some work experience before they enrolled.

[00:28:11] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:28:12] Speaker C: And I was kind of like, you know, I did a year at an I T. Consulting firm before I went to law school, but not so much to speak of as far as a career.

[00:28:19] Speaker A: Sure.

So talk about your legal career while you were doing that.

[00:28:25] Speaker C: Yeah. So I think that, you know, going to law school was, was great. I love law school. And you know, the, the body of work that you're learning about, constitutional law, federal rules of evidence, criminal law, contracts, real estate, but the only one I could have done with that was will's wills and trusts. You're taking tax work. And it wasn't so much the body of work or like specific facts I learned that I find helpful now. But it is the way of thinking, which has been huge. I mean, a typical law exam involves issue spotting. Right. So you take torts, for example, which is the law of suing people. A typical law school exam is they give you a set of facts. And it usually involves somebody gets into a cab, tells the cab driver to step on it, he drives through a construction site, you know, but the construction site didn't properly secure the site. The crane operator drops something on the car, and then you hit a woman. And then the question is, who's suing who? Who's going to win? And what are the defenses? Right.

And being in that kind of vague area where you're seeing points and counterpoints, appreciating both sides of an argument, that's the space you live in.

[00:29:34] Speaker A: Gray area.

[00:29:35] Speaker C: Yes. And development is a lot of things, and a gray area is most certainly one of them. And so, you know, being able to be comfortable in that Vegas and also appreciating that in, in law school, there's no one right Answer. There are just answers that are more right than others.

Right. And then, and even with the Socratic method, hearing a professor or a lecturer give two diametrically opposed arguments one after the other, and each one is equally convincing, you start to appreciate other people's perspectives and other points of view, which in negotiation on a day to day basis for me, I found to be really helpful.

[00:30:12] Speaker A: Well, the question I always have with law, and I studied a little bit undergraduate, is the ethical question. And so when you know that your client is guilty and yet you're willing to defend them, you give them, you know, it's more or less a right that you're giving them, but in your mind, how can you really ethically support and you know, know when you really know that somebody's guilty?

So I guess you have to kind of frame your, your efforts in a way that feels right going forward.

[00:30:43] Speaker C: And what they will tell you in school, and we talked about this in law school, which is a way to think about it, is you're not defending the defendant, you're defending the burden of proof in our Constitution.

[00:30:53] Speaker A: Yeah, there you go.

[00:30:54] Speaker C: Legal system, that's what you're defending. Right. If you were just throwing the towel, then that what it means to be beyond a reasonable doubt starts to slide.

[00:31:02] Speaker A: Right.

[00:31:03] Speaker C: So it's that advocacy, you know, and, and a lot of times too, arguing points that you're not necessarily comfortable with, but you're arguing it because it's a corporate prerogative to protect your company.

[00:31:15] Speaker A: Right, that's right.

[00:31:15] Speaker C: And you got to remind yourself, I'm not, I'm not representing Matt Hard, I'm representing TR. Residential.

[00:31:20] Speaker A: Yeah, right.

[00:31:21] Speaker C: And so that, I think having that mindset coming out of the legal experience has been, has been really helpful. And I also, I think, you know, the writing style has been helpful. I use that a lot.

It's called, it's called irac, which is the format. I think it's issue, rule, rule, exceptions, application and conclusion.

[00:31:45] Speaker A: Yeah, it's like a brief. You're doing a brief.

[00:31:47] Speaker C: Yeah. And you start, you start to think in terms of outlines. And so communicating has been helpful. Again, the kind of documents and negotiations I'm doing now I didn't do when I was practicing or when I was in law school.

But I do think, especially in the early innings of my career, those documents were more or less, I guess, demystified for me. I wasn't quite as intimidated by them because I've been on the side of preparing big documents like that. And so I think the edge that it may have given me is I'm probably a little bit more comfortable overruling our own attorneys. Not necessarily overruling, but, but, but, but being comfortable saying, hey, I understand, I understand your point. I understand you're trying to protect us. But on the balance with these facts here, and here we are, okay, accepting this risk.

I was very comfortable at a young, relatively young age. Now, now where I'm at most people, if you spend enough time with legal documents, get to that point. But I look back in the early innings of my career, that was all very helpful for me. And so I think the legal training was great for what I'm doing today.

[00:32:47] Speaker A: Well, you know, I think the key is to understand the difference between business and legal decisions.

And I always had that issue with some attorneys when I was in the business side.

[00:32:59] Speaker C: Right.

[00:32:59] Speaker A: That they just, they just didn't understand. There is a point where you have, you can advise, but you're not making the final decision here.

[00:33:07] Speaker C: Right.

[00:33:07] Speaker A: And, you know, and they get into the weeds on the, on the business side. And I said, no, no, no, no, hold on. This isn't your business.

[00:33:15] Speaker C: Yeah. Well, I've also seen the inverse of that, where something I'm sure could be a business issue, and my counterpart will say, well, I got to run that by counsel. I'm like, well, you know, do you.

I mean, who's, who's. What's the goal here? Like, who's running the show? And so the negotiations that I've seen fall apart, and it's only been a few times where the deal just doesn't move forward.

You know, a lot of times it, it is the involvement of lawyers or the lawyer really driving the show. Now, that is a little uncharitable and a little unfair to legal community because I, I do have a healthy respect, and they play a critical role in what we do.

But when. There's no when, when, when the business counterpart is not willing to overrule or make the decision themselves across the board on documents, they're just never going to get done.

[00:34:01] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:34:02] Speaker C: So, you know, you miss.

[00:34:03] Speaker A: And there are times when, when there's something gray and you just say, you know, we're going to take it. We're going to take a run on this and overrule the legal opinion and just say, you know, it might be risky.

And we, but we decided to take that risk. And it's, you know, it's a measured risk, and we're, we're going to take it. We know the risks that could happen. So that's, you know, it's interesting.

So what did practicing law teach you about risk and leverage specifically? I mean, how did you know when to balance it?

[00:34:39] Speaker C: Well, in terms of the risk management, when I first started out as a lawyer, you know, you are learning as you're going, so you assume that every issue is a big issue.

[00:34:53] Speaker A: Right.

[00:34:53] Speaker C: And that's not a very good answer. Right. But in the early.

Right.

[00:34:58] Speaker A: Because, well, you don't know.

[00:34:59] Speaker C: And all of a sudden you're in law school and all of your efforts has been to memorizing the elements of a claim on libel law. And then all of a sudden you get a purchase and sale agreement in front of you and say, hey, can you mark this up for the client?

You learn pretty quick that your role in that is to outline all the risks and then let the business person.

[00:35:18] Speaker A: Make the decision, step away.

[00:35:21] Speaker C: Yeah. And there is such a thing as being a good and a bad client. Right. Some clients don't like to hear it. Right. Or they don't want to deal with it. But the role of the lawyer is, it is not to make the decision on what risk we take is to point out what the risks are.

[00:35:34] Speaker A: There you are.

[00:35:35] Speaker C: Right. And so that can be a tough mindset to shake when you go on the business side. And it's like, because you can talk yourself out of anything and you can outsmart yourself and everything, you can always, of course, you know, underwrite your way out of a deal. I mean, that's easy, but you're not getting bonus points for not doing deals, you know.

[00:35:55] Speaker A: No.

[00:35:56] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:35:57] Speaker A: Nope.

So when did you know you wanted to be on the building side of the business and get into the real estate business?

[00:36:05] Speaker C: So I'd say pretty early. I knew I wanted to be on the principal side of the business. I wanted the weight and the responsibility of being the decision maker. I wanted to be the one that was assembling the team, asking the questions, getting the inputs, making an evaluation. So that applies generally to where I wanted to go. And I knew that now. How the conversation first started with my dad was, was we were circling each other for a while. He came out to visit with my mom, asked me how things were going, and I, you know, more or less said that I want to do a career switch. I don't think that this practice is going to be long term, a good fit for me. And so I'm looking for a way to get out. And then I started asking him questions about what he does. Right. And literally it was. It wasn't until I was 27, 28, that I really started to understand what he did. And I was like, oh my gosh, like, it's a really fascinating, interesting career, right? So he doesn't say anything. And then I get a call from my brother in law who is a part of all this, who says, hey, you should, you should talk to your dad. I said, why, what, what makes you say that? He goes, well, I was talking to him, he says that you might consider, you know, transitioning careers. And he just kind of casually mentioned that Alcor is hiring, but he doesn't want to bring it up to you because he doesn't want to put pressure on, you do. And I'm like, well, I don't want to ask him because I don't want to ask him for a job, right? So there was this like reluctance on both our parts. You know, I didn't want to be the son asking for the job, he didn't want to be the dad saying, well, man, you gave it, you gave it a good shot and now come and work, you know, alongside me. You know, that's just what, what the dynamic was. But ultimately I broached the subject and he said, look, like you'll apply, we'll give the resume, you're gonna do all these things. Here's what look like. And we spent a lot of time kind of chatting about it. But the thing that we focused on a lot, especially when once I passed the SNP test with his partners because he had to clear it with everybody. And I don't hide from the fact that there's definitely, I mean, this is nepotism, right? There's really no way to spin it. I'd like to think at that point I had, you know, between the legal degree and the experience I had had in the, in the, on the real estate law side of things, enough qualification to pass a squint test on whether or not I deserve to be there. But I carried a pretty big chip on my shoulder in the early parts of my career. I was insecure about it, right? And I was very mindful of the impacts that me joining could have on morale within the office, that transition. Right. And he stopped being dad and he started being Bill. And that stuck to this day. I still call him Bill. I should probably go back to dad. But he was Bill in the office and I, you know, when we'd be in meetings, I was reluctant to say what my last name was. Right. Because I didn't want to.

I, I assume that others, fairly or unfair? Fairly. I assumed others were assuming. The only reason I Was there. Was because of my dad and what. My last name?

[00:38:53] Speaker A: Yeah, yeah. What, what type of law did you practice when you made that transition?

[00:38:58] Speaker C: So, well, I would say big astronaut, all this. I practiced for a grand total of 18 months. Right. So I wouldn't say that my contribution to the legal world were, you know, I'm, I'm no Perry Mason. Right. But half of it was, was, was corporate work. So some, some light M and A. We had a healthy IP practice out there. So some licensing agreements, employment agreements, things like that. And then 50 of it was on the real estate sides and it was mostly acquisitions and dispositions.

[00:39:22] Speaker A: So you're doing transactional work.

[00:39:24] Speaker C: Yes.

[00:39:25] Speaker A: So you, you knew the real estate industry a little bit.

[00:39:28] Speaker C: Yes.

[00:39:29] Speaker A: From doing that. Okay, so this wasn't a complete change. Is that like you were doing, you know, litigation?

[00:39:37] Speaker C: Right.

[00:39:37] Speaker A: Going, going into real estate. Yeah. Okay.

[00:39:40] Speaker C: But, but it was a sensitive thing. Right. For me. And, and you know, one of the things I'm most proud of is that when I joined, there was another development associate there by the name of Josh White, who's still at Elkhorn. He and I became and still are dear, dear friends. Right. But you can think of a scenario, oh, God, here comes the boss's kid. Right. Like, how's this going to go? A scenario where that's not a good dynamic. And so I think both my dad and I did a, did a good job that I'm proud of, of making sure that, you know, we didn't create issues inside the company. And for the most part, on a day to day basis, I reported to Harmer Thompson, who now runs the office of EL Corp. Yep. So. And that was all by design. Yeah.

[00:40:20] Speaker A: So you were at. How long were you at Alcor?

[00:40:23] Speaker C: I was at Elcor for seven years.

[00:40:26] Speaker A: Yeah.

So what was the steepest learning curve there?

[00:40:30] Speaker C: Construction.

Hands down.

Not even close. It was, well. Well, I shouldn't say everything because going from law, where you just see a little sliver of it, and even within the law that I was doing, I was seeing, you know, a tiny sliver of the, you know, kind of real estate transactions. I wasn't doing development work when I first joined. I kept a notebook where I, where I, you know, took all my meeting minutes and I would underline everything that I didn't understand and then go home and, and spend some time on the Internet and figure it out. So that's what my day really started was at the end of the work day to really get up to speed. And let's just say that that notebook Which I still have. The whole thing's underlined, right?

And like, you know, between the acronyms and, you know, all the, the, the, the code words.

I mean, things like cantilever. What is what, like pile driving? Like, is that a, is that a wrestling move? Like what's, what's. What's pile driving? Right.

So I would say that the construction side of it.

[00:41:26] Speaker A: Did you ever go have a beer with your dad and say, come on, dad, tell me what's. What is this stuff?

[00:41:31] Speaker C: So I would say, speaking of the nepotism, the, the one advantage that I really have, my dad really helped me. I don't necessarily believe the expression that there's no such thing as a stupid question. Like, we all know that it's definitely question. If I go in there and ask what I, what a, what a cap rate is, like, that's. I, I know that that's a stupid question. Question I'm not going to ask him. Right. But with my dad, after business hours, I was comfortable enough with him to ask questions that were probably pretty stupid. So I had him on the bat phone to kind of help me get up to speed.

I didn't take too much advantage of that, but that, but that was huge.

[00:42:08] Speaker A: For me, of course.

[00:42:10] Speaker C: And I tell people today on the construction side of things that in terms of backgrounds, if I could trade my legal background for any background, it would be in construction.

Just as far as where our risks are, you think about development and the cap rate premiums that we get for taking construction risk, our biggest risk being schedule and hard cost.

What better discipline to be an expert on than construction if you want to be a developer?

[00:42:37] Speaker A: Well, we can get into the development business quite a bit. I know it's interesting that you say that construction was your biggest learning curve, but in my talking with many developers, the entitlement process usually was the one that caused them the most angst in their careers. But maybe not with you. Maybe the entitlement was something that was a little.

Because of your legal background, you had a little better perspective of it.

[00:43:05] Speaker C: Yeah, it was. The stress of the entitlement is certainly not to be underestimated and definitely the most sensitive thing. But I also think about where we get tripped up on getting to a closing assuming the entitlements are in place. You know, the construction site logistics and civil engineering side of it is very much tied to entitlements. If you define entitlements as, you know, final site plan. Right. Like Getting through a 4.1 is one thing in Arlington county, which is you know, the rezoning, the community meetings, all that. But getting through the CEP is another.

[00:43:34] Speaker A: Right.

[00:43:35] Speaker C: And so, but I would define that as entitlements.

[00:43:39] Speaker A: Yes.

[00:43:39] Speaker C: The things that we get in trouble on or the surprises we have are typically site and construction related.

Having someone on your team who has that expertise is worth its weight in gold. I mean, seriously. And also when I, if I look at whether it's hiring or what the backgrounds are, when I talk to young people. You take a project manager at one of the big GCs here, right? What by virtue of them being a PM on site. What does it tell me about them? It tells me that they're very organized. Tells me they can make their way around budgets and accounting. It tells me that they can administer contracts, it tells me they're good at managing relationships and it tells me that they're really good problem solvers. That all sounds a whole, you know, a whole lot like being a developer. Right. And so that's a career path. I think when I talk to young people, it's like, don't, don't rule that out. Right. Not all paths in development are coming from, from the finance side. And our biggest risk is execution hands down. It's the only thing we control. So you should be pretty, you try to be pretty good at that.

[00:44:39] Speaker A: Yep. Well, you want to get that done. But there's a whole other set of things, you know, securing tenants for your property, going to get financing and range capital for the, for the project. I mean there's just a whole series of things that are, you know, as an institutional developer, which you've been in your career, part of that is a little easier.

Whereas, you know, if you're a speculative, you're, you went out on your own, you'd have a whole different outlook looking at development.

[00:45:12] Speaker C: Yeah. And I've noticed that even over time since kind of entering the industry in 2012, you know, the cost to play ball are so exorbitant. I mean, obviously I gave the example of the typical pursuit cost, but I'll give you another. For me, for me to do an intake meeting with one of the counties here, I, I won't say which one it is. It's $25,000 to have a meeting to see if, if we even have a path to get through the entitlement.

[00:45:36] Speaker A: So imagine yourself on your own.

[00:45:38] Speaker C: Exactly, exactly.

[00:45:40] Speaker A: It is so doing that to step. Okay, Mad Hard Incorporated.

[00:45:44] Speaker C: You start out, it is so capital intensive and then, and then you don't even get to the guarantees and what it takes to get institutional. Exactly right.

[00:45:53] Speaker A: So my, for listeners, my interview with Tom Busuto talks about that. Just issue that right there, what you just talked about when he started his company and he had to go and tell his wife that we're going to go guarantee a construction loan on his first project personally with their entire estate on the line. That's, that's a tough conversation.

[00:46:15] Speaker C: Oh yeah, no, I have a lot of respect. Doesn't matter what the size of the, of the project is. It could be a small townhouse development. Anybody who puts together a deal and executes and closes on their own is a remarkable achievement. Right. Because we have all institution developers the warm cozy blanket of a, you know, credible, highly liquid guarantor. And that's something that we don't have to think too hard about. Right. We don't have to think too hard. I mean we think hard about those pursuit costs with like, you know, the $4 million, you know, the cash is there, it's just whether or not you're willing to put it at risk. But we don't have to think about going outside, you know, the firm to raise that pre development capital. We don't have to think about COGP, we don't have to think about our 5 to 10% co invest. Those are all advantages that, that I do not take for granted. And you know, especially if you're talking about it's very easy and let's call it your early mid-30s after you've got a, you know, two or three deals under your belt on the execution side to say, hey, this is so hard, you know, I can do this. You know, it's like, well, there's this pesky thing.

[00:47:18] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:47:19] Speaker C: That can kind of stand in the way of that. But not, not to throw cold water on people's entrepreneurial dreams. It certainly happens. It just feels like it's, it's getting harder and harder.

[00:47:30] Speaker A: So let's shift out of some deals and some experiences that Elcor, which, which project at Elcor fundamentally changed how you think as from law into development.

[00:47:42] Speaker C: Yeah, yeah. I look back very fondly on the deals that I was able to do at Elcor and there's obviously the first one which fundamentally changed how I think because it was my first deal. So it got me to like a baseline on how hard this actually is. But I think what, what the deal that, that changed how I thought was the second deal that I did which was the more street deal in union market.

And it changed how I think because number one, it was the first year where I could, I Actually started seeing patterns and actually felt like I was able to manage risk. Right. Because on the Edison deal I was just taking it as it came. Right.

[00:48:16] Speaker A: And I assumed talk about those deals a little bit and what your thought process was.

[00:48:23] Speaker C: So we were one of the first movers in Union Market as far as ground up, multifamily development and mixed use deals. Ian's obviously come in and, and, and redone the market. So that was an anchor. They had, you know, assembled a whole portfolio of, of retail stalls and properties within Unimarket and it assisted in, you know, the small area plan in the county. So I was acting more or less as a, as a master developer in the whole thing. And so we did a deal with Eden's where we were going to be the first ground up development which is at the Corner of, of 4th and Florida Avenue. And it was going to have a ground level Trader Joe's. And we were looking at it. This is before Union Market was built out. And you know, on the one hand, you know, the bull case was when Union Market takes off, this is the place that you're going to want to be and we're okay with that. On the flip side, PD Market doesn't, you know, if the dream doesn't come true or we can still tell ourselves that we're on the outskirts of Noma as our downside. So that felt good as far as being the first location to develop. But that deal was probably one the most complex deal that I've done and it also happened to be the first one I did. You know, it had everything. Yeah, environmental contamination, unrecorded utility lines crossing the site, servicing a neighbor who was not interested in us developing lot line development, you know, small deal. Right. 187 units. So those types of deals have a very, very small.

[00:49:45] Speaker A: And you negotiate a Trader Joe's retail lease, among others. I imagine.

[00:49:49] Speaker C: So we did not. And that's where the complexity came through. So Eden's, the structure was that they were going to own.

You know, at closing we created the Air Ride subdivision.

[00:49:58] Speaker A: Oh, okay, held on.

[00:50:00] Speaker C: So we built within there. So we acted as the master developer of that site. But they own the retail throughout the whole thing.

[00:50:07] Speaker A: So that adds even more complexity to it.

[00:50:09] Speaker C: Yes, yes. Which might be another question you have later on and I'll get to the mixed use of. But that was, that was deal number one. Deal number two was More street which was a couple blocks away.

It was a multi, multi parcel assemblage. We thought that it was right down the middle of the fairway as far as what the small area plan called for in the pud. And we took that deal down as is where is right, which is the types of risks that if you can take those risks, it's a really powerful way to get market share. That's probably the way we're set up here, probably not the types of risks we're comfortable making at tcr. But what that deal taught me was, number one, being able to apply the lessons learned and start to identify patterns and start to get a little swagger, right. Get a little confidence in the decisions that we're making. But number two, it taught me that when you don't have an eject button on a deal because we've already closed on it, you'll surprise yourself at how scrappy you get and how hard you work to solve problems. Because a whole lot of things happened on that deal post closing that we were not counting on that, you know, if we had had an eject button, maybe we would have been tempted to press it. And I'm talking about things like, you know, we got appeal during the pud, right. We, during the course of the, of the, of the pud, it became clear that we're going to have to run a public right of way right down the middle of our site, which creates all sorts of issues. We got threatened to have the Little Tavern. There was a restaurant, it was a subway, but it was the old Little Tavern hamburger chains. We got threatened to get that historically landmarked, which as you know, could send your, your pud, you know, backwards many, many steps. So we opted to do the course of pud. We volunteered to move the building off site during construction, excavate, build the garage, come back up, build the building and then slide it back in. Right. Wow, that was a problem solving. It had been done before, but all these things kind of collectively not having any other option again kind of showed what you're capable of in terms of things out. So that was my fundamentally changed. How I thought is that don't underestimate yourself now Scrappy. You can get.

[00:52:19] Speaker A: So getting into the mixed use side when is mixed use additive and when it is just complexity.

[00:52:24] Speaker C: Yeah, I would say that, you know, mixed use by definition isn't necessarily going to be, you know, rise to the level of the juice not being worth the squeeze. It's not the mixed use element. It's the mixed ownership element. That's when you start going down a path where complexity is really. You're talking about, you know, guarantees, liquidated damages. What happens when the Building burns down all these things.

Add a level complexity where I.

Oh yeah, oh yeah. Rea. But if you control everything and you're able to do it with one source of capital, I don't. Yeah. Other than design complexity, you know, there's nothing that would preclude us from looking at those sorts of deals as long as, you know, take retail for example. As long as our deal still works or it's a scenario we can live with if the rental income on the retail is zero. Right. That's how we'll stress test it. Usually once we get above 15,000ft, that's where that starts to break down a little bit and we might actually look to put bring in another partner. But again, the, the, the, the ownership side of things.

You know, I honestly. But before this podcast we were, I was on a call on a horizontal mixed use. And it's the same bucket of issues and it's not a particular like on paper, not a particularly complicated deal. Right. But you know what happens if you don't deliver on time? You know, who's going to be responsible for this? How are we going to allocate the costs?

[00:53:46] Speaker A: Right.

[00:53:47] Speaker C: And then you realize that in a document that you negotiated for allocation of electrical bills, the way that your electric meter is set up doesn't account for that. And so there's no way for you to segregate utility bills. And so how all those things make their way into the practical reality, I'm comfortable saying that one complicated mixed use deal with separate ownership is probably worth one and a half to two straight up market rate deals. As far as effort and man hours.

[00:54:14] Speaker A: Well, you just learned what the retail business has been all forever. I mean, retail development is always mixed use in many ways.

So even if you're doing a straight shopping center, because you're doing sometimes ground leases on pads, you're doing, you know, different deals with anchors and you would do strip centers and sometimes there's all kinds of complications. So vertical even, you know, horizontal or vertical multi, multifamily to me is probably one notch below retail development as far as complexity.

[00:54:47] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:54:47] Speaker A: And you get.

[00:54:48] Speaker C: I would say, and I would say too, you know, it's, it's undeniable, especially in an urban context, that if you have ground level retail that it's going to drive value above. But the issue is that, you know, especially if it's competitive bidding process on land value, you're already counting on that rent pop in your underwriting, which means you're paying more for the land.

[00:55:08] Speaker A: Yep.

[00:55:09] Speaker C: I don't Know, kind of end up in the same place. Now, if you're a landowner, considering do I do mixed use and you got the same basis.

[00:55:15] Speaker A: Right.

[00:55:16] Speaker C: Or, or do I just do amenity space? Of course you're going to pick mixed use regardless of the design complexities.

[00:55:22] Speaker A: Again, well, your, your residents are going to tell you they want certain services on site if they can get them. And so that's, that's the value add there that sometimes doesn't show in the economics. It's, you know, it, it helps in your lease up things that you don't really, it's, you know, without it, you couldn't underwrite what your absorption pace is probably.

[00:55:43] Speaker C: That's right.

[00:55:44] Speaker A: So. And it's hard to measure that.

Right?

[00:55:47] Speaker C: Right. Yeah. No, there is an intangible.

[00:55:50] Speaker A: Right, exactly.

[00:55:51] Speaker C: But it's a pain, It's a pain doing retail, but, you know, a lot of respect for that side of the business.

[00:56:00] Speaker A: So what discipline do you do do, do you now insist on earlier than.

[00:56:05] Speaker C: Before when we're doing due diligence? The, the type of things that, that I become more focused on accelerating, you know, specifically is civil and utilities.

[00:56:16] Speaker A: Interesting.

[00:56:17] Speaker C: There's a lot of optional kind of due diligence things you can do and obviously you have an incentive to keep your due diligence costs low. But you know, the reality is if you're going to do a, a full thorough DD exercise, it's going to be at least $100,000.

[00:56:32] Speaker A: Right.

[00:56:33] Speaker C: Just, just to get to the point where you're ready to commit the real dollars on the design of the I, I.

And, and a lot of this too is a function of the types of deals that we've been looking at, given where we are in the cycle. Right. Underwriting an urban, you know, parcel is a lot different than nine acres in the suburbs. Right. But I, but what I found is, you know, thinking through, grading, thinking through, you know, all the civil things, the site balancing, utility relocations, those are the things that if we're not focused on them early, they can have big, big impacts down the line.

[00:57:07] Speaker A: Oh yeah.

[00:57:08] Speaker C: Especially when it's like, oh, accidentally we, we put tree pits on top of a, of Washington gas line. And because we didn't hire a private utility sweep because we wanted to save $10,000 during gas, guess what? Like, we have to move this gas line, it's going to cost us a million bucks. Like that's the sort of thing if, if you're not doing a thorough underwriting, you can't run into that now you're in the middle of the entitlement and you're moving the goalpost with, with counting or asking for a variance.

So, you know, the, the collective lessons learned seem to kind of consolidate around civil and sight being something that we need to accelerate. But again, it's deal by deal. We're looking at a deal now that is a very creative. It's actually a five over five podium deal. Right. And so you can imagine for that deal, the focus is going to be on code and fire. Right. And so we will, you know, identify extra consultants we normally wouldn't use to run reports for us to make sure that what we think is the case is the case.

[00:58:03] Speaker A: So, sure.

It's interesting. Early in my career, I was a construction lender on a site in Germantown, Maryland. It was a garden project. It's a large one, about 400 units or so.

And the developer client was a home builder. So they, they had not been in the multifamily business before. It was their first multi job and they primarily built townhouses and single family and they ended up putting up two buildings, multifamily buildings, without doing stormwater management first.

[00:58:40] Speaker C: Yikes.

[00:58:41] Speaker A: And we had to have. They had to tear those buildings down and do the stormwater management over again.

So.

[00:58:50] Speaker C: Yeah, I don't know how anybody gets away with anything because we can't get so much of a stormwater management approval on anything until.

And that's what takes forever to get the approvals.

[00:58:59] Speaker A: Well, this is in the example of the 1980s. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:59:03] Speaker C: Of like the phasing and the stuff you got to think about on.

[00:59:06] Speaker A: Exactly.

[00:59:07] Speaker C: Especially when you're making your density assumptions. So. And that is back to the civil work. You know, jurisdictions, especially on the Maryland side, are getting tougher and tougher on stormwater management requirements that really impact. Oh yeah, you know, your, your impervious surface, which can impact your density because it impacts your parking. Right.

[00:59:23] Speaker A: Well, when the 1980s, the environmental laws were a whole lot different than they are today, certainly. So although there was, you know, California, it was ahead of the game. And Maryland tried to follow up, especially in Montgomery county. And they tried to at least. But anyway, so you, at some point, after about six or seven years with your dad at Elcor, although he may have retired in the time frame that you were there, you decided to make a change. So talk about, you know, why you just stepped back and said, you know, maybe I'm going to make a change and leave Alcor and go join the Trammel Crow residential firm.

[01:00:01] Speaker C: So candidly, I was, I was not looking when all this came together. And part of the story of how I. I joined TCR does tie back to our activity in Union Market, because while we were the first deal to deliver right up the street, Trammel Crow Residential was under contract on the Valley, but they were about six to 12 months behind us. And so I had gotten to know the. The market lead here, Robbie Brooks, who had been running this office, you know.

[01:00:28] Speaker A: Yep.

[01:00:29] Speaker C: Really from 2012 to 2020.

Got to know him really well during that process.

[01:00:33] Speaker A: And so Robbie was a ULI mentee of mine.

[01:00:36] Speaker C: Oh, yeah. Awesome. Awesome. Yeah, no, great guy. You know, I kind of saw him as a mentor of me, you know, when I was coming up.

[01:00:44] Speaker A: Sure.

[01:00:46] Speaker C: Market. And so I was not looking. If anything, this was during Covetous. Right. So this is August of 2020. We had just closed kind of the last deal that we had had El core in the pipeline at that point in the cycle, which was the 300m street deal, which was a very complicated. It was still part of, you know, Union Market adjacent. It was on the south side of Florida Avenue. So it's August of 2020.

And at that point, you know, unfortunately, my mom was about two months away from. From. From passing away from cancer. So we knew that in kind of the final. The final months of her. Of her battle, my brother had relocated temporarily back here to help. My sister had kind of relocated after she delivered her third child. So that was one of the silver linings of COVID was that we were all able to work remotely, drop everything, and just all be together. And in the meantime, not to add another layer of darkness to this conversation, but my wife, in May of 2020, was also diagnosed with cancer. And so she had gone through six rounds of chemo at that point. Thankfully, it was Stage 1A, but it was still the kind of chemo like, you know, it was a hammer, right. It was. It was chop stuff. But.

[01:01:50] Speaker A: So had you had children? You had children at that point?

[01:01:52] Speaker C: Yeah, young children. But my wife, to her credit, you know, she was really close with my mom despite, you know, her struggles and not feeling well. We were, you know, she was right about to go into. Into remission. We weren't, you know, we were 90% sure that she was in the clear. But I remember leaving that afternoon to go spend time with my mom, and my wife was like, you know, shooing me out the door door, like, go, go, go. You know, she's lying on the couch and not feeling well. And I got two young kids. So anyway, I get in the car and I'm driving. And by the way, John, this is where all my hair went. Right.

[01:02:23] Speaker A: I had a mother and a wife with cancer.

[01:02:26] Speaker C: My God, 2020 was the year Covid, you know, and then two family members do that. So Robbie calls and he says, hey, man, I know you got a lot going on, but I just got the thumbs up from our investment committee to expand the company and open an operation down in the Carolinas, which is where he's from, covering Charlotte and Raleigh. And in connection with that, we're doing a search and your name's on the list. And so if it's something you're interested in doing, we should talk just like that.

And frankly, I thought about it for about 30 seconds.

I knew the firm.

I also appreciated that the opportunity to take on a leadership role, while not without its risks, does not come around very often. Right. Like I could be. I knew I could be waiting another four or five years to get a call like that.

[01:03:12] Speaker A: And Harvard wasn't going to go anywhere.

[01:03:14] Speaker C: Right, right, right. And, and, and so in retrospect, I think all the stress that was going on in my personal life, that applies to everybody. I mean, life happens when you're working. Right. And so. But life for me just came very fast and all in like, what felt like a six month period.

And I think that the stress of all that also gave me a lot of perspective. And I thought to myself, well, you know, it's not like things could get more stressful, so why the hell not? Let's go for it and take on the challenge of joining tcr. So I flew out to Dallas, you know, did a super day there. I met with Leonard Wood Jr. Who I report to now runs the East Coast. And from that first conversation in August, I started about six weeks later, about four weeks after my mom had passed away. So it was intense. It was an intense period of time, but that's how it all came together.

[01:04:04] Speaker A: So since you've worked for both companies, contrast the style and difference between Elcor and Trammel Crow Residential. How would you define the cultural difference and how they look at deals? Just out of curiosity.

[01:04:17] Speaker C: Yeah. I would say the culture is remarkably similar. And it's funny you mentioned all roads lead back to Dallas. The L and L core stands for Lympro, which was a spin off.

[01:04:28] Speaker A: That's right.

[01:04:29] Speaker C: Lincoln. Right.

[01:04:30] Speaker A: Which Lincoln property? Which is Trammel Crow. Yeah, yeah.

[01:04:33] Speaker C: Has TNA travel Crow. So it's like, it's crazy to think that that's the case, but I had an exceptionally good relationship with the folks I worked with at Elcor and I look back very fondly and I'm grateful for the opportunity to work on as many deals in a shorter period of time as I did. I'd say the biggest difference was we were working with as close to discretionary capital as you can get. It's not, it was not discretionary that we were in a fund structure, but we did have a programmatic relationship with one of the larger pension funds in the country.

And so we did not have to spend too much time thinking about third party capital where we knew because our mandate was to do complicated urban ground up, core transit oriented development.

I would never say that it was an afterthought on where the capital was coming from because we had our own process, but we knew that if we could get approval internally, we were good to go. Right. So now in contrasting where I am today, on the one hand, we do not have that kind of bucket of capital to go out and do the full equity cap stack and we will fund our deals 9 to 10 and basically raise capital on a deal by deal basis. So that's a fundamentally different focus that I have now. And one of the downsides to those is obvious, is that you don't know who your capital is going to be on a deal until you've actually raised it. But the upside is that we can move with the cycle and move with capital markets demands and there's a lot of capital.

And so if right now the flavor du jour is basis oriented, modestly sized suburban service park deals, which is what we, the last three deals we closed, that was the profile. That's what we're going to do. As the market starts to pick back up, we're going to start doing the wrap deals again and the podium deals, then ultimately the high rises. And so having that flexibility kind of a across, you know, that spectrum is different than when I was at El Cor. But I say, you know, the big things are the same, the day to day is a little different. And also another big difference too is that we have a self performed general contractor here which is a lot different than what I was used to. We did everything third party at elcor, but we had in house property management and here it's flipped. We do third party property management and we do in house general contracting, which is a, which is a big difference, I will say. And I actually candidly think it's an advantage that us and groups like us have because we as a general contractor can take risks on pricing that a third party GC can't and probably shouldn't be taking.

[01:07:02] Speaker A: Well, it's interesting. One of your competitors, Folger Pratt, decided to go out of the construction business and that was the roots of their company.

And it's kind of interesting. I asked Cameron Pratt about it and he said, you know, it just got to the point where the risks didn't make. Make sense for us in our platform.

[01:07:20] Speaker C: Yeah.

[01:07:21] Speaker A: So we wanted to be more nimble and not have to be, you know, take the risk of the construction side. So. And he came from.

[01:07:29] Speaker C: It's, it's an interesting discussion and obviously you need a certain level of scale to have the numbers.

[01:07:34] Speaker A: That's right.

[01:07:35] Speaker C: Because you're not going to be able to charge all the people it takes to run.

[01:07:39] Speaker A: That's right.

Big overhead. It's a big overhead issue too.

[01:07:43] Speaker C: Oh yeah. And the other thing too, I mean the original sin of, of any in house self performing platform is the risk that, you know, you will, you'll fall out of marketing or on. Because in any given year we're never going to do as much as a Davis or, or a Clark. Never. So you can lose your touch point on where the market is for the pricing. But you know, if, but I'll give an example. If we think that a deal is going to cost $100 million. Right. In hard cost, I mean that'd be a really big deal. Just using round numbers. If we think it's going to be $100 million, we might. But, but our capital partner, bank, etc. It needs to be at 97. Right. In order to get to closing. Well, TCR might make the election that, you know what, we're going to guarantee the number at 97 and if it ultimately ends up being 100 million, we can make the option of contributing a portion of our fees or funding the cash overrun or maybe we'll have a good buy and we'll use that. Right. A third party GC will never make that calculation, nor I expect them. Of course they have a different evaluation on the deal. We're looking at, you know, in the pro and con bucket. Pros being, you know, fees, potential upside and cons being the write off we're going to take if we don't close. And that's a risk we're taking.

[01:08:55] Speaker A: Right. In your pursuits of projects and sites, that's an advantage you bring to the table because you have more flexibility when variables come up that cost control, you have a better handle of that than somebody who's hiring a third party.

So there's an advantage there.

So Obviously in the competitive real estate business, you want to have every advantage you can possibly get to get deals done.

[01:09:24] Speaker C: Our ability to lean in on that part of the cost stack is a big advantage we have.

[01:09:29] Speaker A: Yeah, I imagine. And you've learned a lot. I imagine being there having in house construction as opposed to hiring third party contractors. Yeah, I'm guessing. Oh yeah, yeah.

[01:09:41] Speaker C: Although, you know, I had a great relationship with our third party gcs. But I would say, yeah, having somebody in the hall right next to you is different than it being an outside firm. Yeah.

[01:09:50] Speaker A: I mean, if you're looking at site constraints on a site that you're trying to figure out, you can walk down the hall and say, okay, tell me what I have to do here to try to make this work. Right. Or is this, is this schematic work?

You know, is this physically going to make sense and can we, can we cost this out to make it work?

[01:10:09] Speaker C: Yeah. Or, or more likely the conversation is, here's what I have to agree to. Please tell me you can make this work.

[01:10:15] Speaker A: Exactly. Yeah.

Yeah.

So how do you take stewardship of an inherited pipeline?

[01:10:23] Speaker C: Yeah. So when I, when I joined, it was, it was 2020. Right. So. Right.