Episode Transcript

[00:00:09] Speaker A: Hi, I'm John Ko and welcome to icons of D.C. area real estate, a one on one interview show featuring the backgrounds, career trajectories and insights of the top luminaries in the Washington D.C. area Real estate market. The purpose of the show was to explore their journeys, how they got started, the pivotal moments that shape their careers, and the lessons they've learned along the way. We also dive into their current work, industry trends, and some fascinating behind the scenes stories that bring unique perspective to our industry. Commercial real estate.

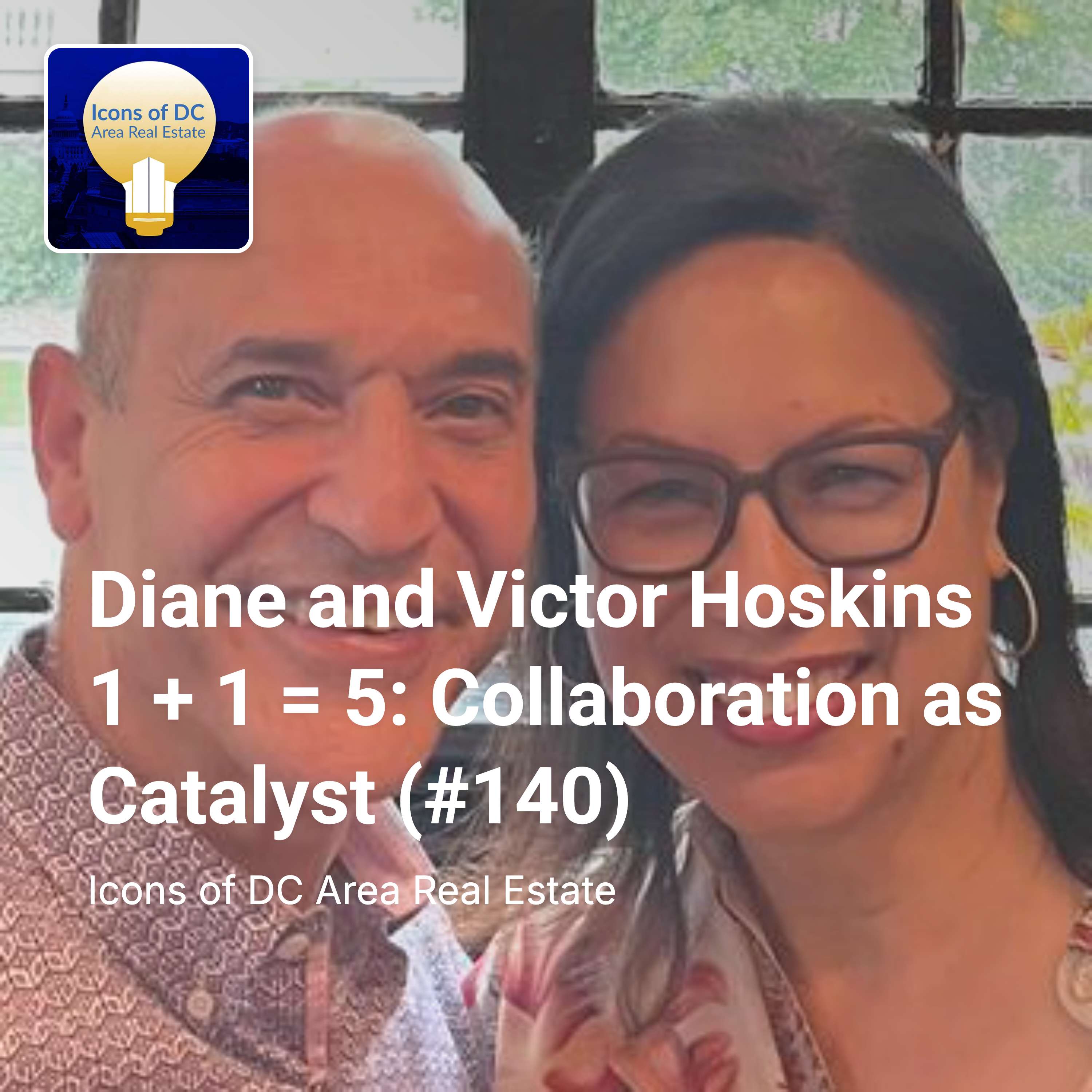

[00:00:47] Speaker B: Welcome to a very special episode of icons at D.C. area Real estate featuring the powerhouse duo Diane and Victor Hoskins. In this insightful interview, we dive deep into the forces that shape their careers and philosophies. For Diane Hoskins, who's the global co chair of Gensler, she traces her foundation belief in architecture back to the Chicago skyline and childhood creativity, explaining how her experience as a developer at Olympia, New York was critical to her perspective on design innovation and leading the world's largest architectural firm.

You'll hear her essential advice for young professionals that budget and constraints are powerful tools that create the innovation in design.

For Victor Hoskins, the renowned economic development expert provides a masterclass in public private partnerships. Drawing on his experience from MIT and his roles in Maryland, Arlington and Fairfax county, he details how he transformed Washington D.C. 's finances as deputy Mayor by treating the city as a business and executing transformative projects like City Center D.C. and the Wharf.

Victor also reveals why talent from then on would be currency of economic development in securing Amazon HQ2 for the region.

Together, the couple shares their multidisciplinary approach, their focus on regional collaboration, and their joint mantra for success, which is get wisdom. And with all that, getting understanding.

This conversation offers essential wisdom for anyone in the built environment, highlighting how the Washington D.C. area is unique for fostering careers of consequence.

And without further ado, here is Diane and Victor Hoskins.

[00:02:56] Speaker A: So Diane and Victor, thank you for joining me. For icons of D.C. area real estate, this is a very special interview and I'm very, very pleased and honored that you both would have joined me on this podcast.

So Diane, early visual inspirations like the Chicago skyline and playing with Legos like it was a job fostered your belief in the power of architecture. How did these experiences lay the foundation for your perspective on designing the build environment for people?

[00:03:26] Speaker C: Wow. Well, first of all, John, it's great to be here. Thank you for inviting Victor and I. This is fun.

So, yeah, I mean I'm, you know, grew up in Chicago and you know, you can't live in Chicago and not be, you know, always kind of reminded of architecture and buildings, and you just see them everywhere. You're not even thinking about, you know, that there's buildings there. It's the only place you ever knew. That's what you see as city and home and, you know, great.

So I think that was, you know, one of the seeds and.

And then really admiring how beautiful the city was as well. I mean, Chicago is and was the most beautiful city in the world. And having been around the world a lot in lots of cities, I think that's true still. I think that's true. But, yeah, I mean, it really. Chicago shaped me. And so that's the nurture part. And then, you know, I guess.

I mean, my mom is very, very creative and studied art herself. And so, you know, my home life was very much on the creative side. My mom really fed our interests in every way possible.

[00:04:45] Speaker A: So both of you are among the first generation of your families to attend a university. How does honoring the family legacy influence your decisions regarding philanthropic investments in educational infrastructure, such as your specific $50,000 gift supporting the conference space at the Fuse at Mason Square?

[00:05:03] Speaker D: Yeah, well, you know, like Diane, you know, being first generation, you know, it is a shift. You know, had I experienced someone that was in my family that had gone to college, I think I would have viewed college very differently. But it is a challenge for someone who has not had that in their home before, where someone talks about curriculum, books and academic achievement. And most of what I got from my mother, who was actually Italian, and my father was African American. So that was a very. They met during the war.

And so coming to America for her was really great opportunity. So that's what's on her mind. And my oldest brother and sister were born there, but the other four of us were born in Chicago. So we got this family of six, and no one had really had college experience. So it was a very different kind of environment. But what my mother said to all of us almost every day, if not at least every week, was, you're going to college. That was it. So everybody was on a college track, and there was no way that we weren't gonna be headed to college. The important part of this, though, is the giving, because what we do know, and both Diane and I experienced this, if it was not for others who thought of people who did not, who had the academic capability, but not the financial capacity, that whole paradox, that difficulty. You have this incredible skill, but you can't realize it because there's not enough Financial support. And it made a difference to me. It made a difference to her. So we look for opportunities to do that, to give back where we can support. And so we consistently give to my high school to kids who are first generation or have outstanding academic achievement, but very low income, and that's a target for us. We want to help those kids because we were those kids, and it makes a big difference.

[00:07:00] Speaker A: How did you go to Dartmouth? Coming from Southern California, I guess is my question. I mean, it's an Ivy League school, which is obviously a good school.

[00:07:07] Speaker D: Yeah, well, it was interesting because my.

My focus was actually on California schools. Of course, I got into UC Berkeley, ucla, and, you know, it was really. I was gonna be in California, but I had a list of schools that I got into.

I got on the phone with my brother, and I told my brother, I said, these are all the schools I got into, and I think Dartmouth was the fourth one on the list. And he said, you're gonna go there? And I said, wait a minute, you haven't heard the others? He said, no, that's where you're going. He said, because that will change your life. He said, you will be a different person when you come out of there. You. He said, those other schools are too close to home or they're too familiar for you. They're not going to challenge you. You need something that's going to challenge you and make a difference in who you are, ultimately. And he said he believed that that would be it.

[00:07:51] Speaker A: Your first semester. There must have been a culture shock.

[00:07:53] Speaker D: I imagine it was.

Yes, it was a culture shock. A weather shock.

[00:07:58] Speaker C: You named it.

[00:07:59] Speaker D: It was a shock. But it was. But it was all good for me. It was a good challenge for me. It was a good way of really understanding my limits and really kind of, you know, because I actually played football my freshman year.

[00:08:12] Speaker A: At Dartmouth.

[00:08:13] Speaker D: At Dartmouth, yeah. Yeah, yeah. But after my freshman year, I dropped football because it took too much time. I didn't have the ability. There were a lot of kids that had the ability to, you know, to do the classes, which were extraordinarily difficult, but also do the physical involvement because, you know, you're lifting weights, you're training, and it just. It took too much out of my freshman involved.

[00:08:35] Speaker A: My son swam at Princeton, and so same deal. And swimming is even.

Maybe even more of a commitment.

But the coach said, academics first, and that's the way the Ivy League looks at things, which is interesting.

[00:08:50] Speaker D: Yeah.

[00:08:51] Speaker A: But that's a great experience.

So, Victor, how does combining formal city planning training from mit, with your real estate finance background, allow you to effectively navigate complex public, public private partnerships and advise on current real estate market transact, transition away from older class BC products. So I'm throwing you right into the real estate industry now here.

[00:09:15] Speaker D: Well, you know, it's interesting because, you know, my, my skills in real estate actually came from my graduate program at mit.

[00:09:22] Speaker A: Interesting.

[00:09:22] Speaker D: They had a financial analysis for real estate, economic impact analysis. They had urban impact analysis. They had all these courses that basically gave me the skills market analysis, gave me the skills to deal with real estate. The formal city planning part, I did an internship and a fellowship at the Boston Redevelopment Authority. So I was able to do the academic, see the planners in action, see the real estate. And what I learned from that was how complex it was. Well, how complex the permitting portion, community engagement is and the transactions themselves were.

So I think having sat around different parts of the table, I learned that everybody had an issue. No one got off easy. It was hard for everyone. Everyone had a pressure or risk. And I think that because I understood that, and then in terms of my experience, I actually went into real estate. I worked for a publicly traded real estate company. I worked in private equity. In real estate, I worked for a very wealthy person where I worked on his portfolio, but I also worked in, in the government. I worked for transportation property, doing acquisitions of real estate. So I was on all these sides of the table. And I think every time I had an experience, I learned something new about the risk and the pressures on the other side. So when I sat down at the table, I thought of the other person in what they were going through and tried to figure out, okay, so given their situation on this side of the table, what can I do to enhance both of our opportunities?

Not give them something that they didn't deserve, but give them the things that they did deserve or need that I could provide. Like, don't hold back things that I could provide. If I could provide an introduction to an investor, I did it. If I could help them navigate their way through permits, I did it. But when I was on the other side, if I was working for investors, I was always looking for the person in the planning department that was more cooperative, that was more. That's not impossible, but it's unlikely, but let's see if we can do it. I search for those people. And I think that that having gone back and forth on both sides of the table, almost half my career in the public sector, half in the private sector, I kind of understood that everybody has pressure, everybody has complexity. No One gets off easy.

[00:11:39] Speaker A: You just gave a negotiation seminar with that, that response. That was outstanding.

That was really interesting because that's exactly how you negotiate what you just said. It's phenomenal. And I'm gonna say that your experience, your undergraduate degree, I'm gonna guess at Dartmouth, gave you that multidisciplinary approach, the idea of looking at every side, looking at all angles and trying to figure things out and looking at things from more of a global perspective when you're sitting down instead of kind of a narrow view.

Am I off with that?

[00:12:17] Speaker D: You're spot on.

[00:12:18] Speaker A: So, Diane, how did pursuing an MBA from UCLA after shifting your focus to corporate interior design enhance your capacity to lead the world's largest architecture firm and champion research based innovation like Gensler's Workplace Performance Index?

[00:12:36] Speaker C: Wow, that's a huge question.

You know, it all kind of for me, you know, and maybe I learned this from being my mother's daughter, but, you know, she always was, you know, start with what you're interested in. Start with what is your passion, what you like, you know, today, not a decision from the past.

And, you know, coming out of mit and I ended up working for som, which was at that time the largest architecture school, Chicago based, and certainly designing the tallest buildings, the most adventurous and interesting projects as well. So that was a great sort of, as we in architecture will say, it was a great graduate school because you just learned the craft. You learned what is a building of that.

[00:13:31] Speaker A: You know, was there a mentor there that you kind of picked up from.

[00:13:34] Speaker C: Just out of curiosity, you know, I had the good fortune of, you know, I was hired by a guy named Art Muschenheim. And he pretty much hired anyone who worked in the Chicago office of som, were all hired by Art Muschenheim. You know, he kind of had the, you know, the touch of who should be in and so on.

And, you know, when I was hired, I was brought into and, you know, again, they had a studio system.

And each studio, the office itself was a thousand people in that Chicago office alone, and the Studios were about 50 people each. So you had, you know, two on a floor and so on and so on.

So I was in the studio of a woman named Diane Legg. And at that time she was known as Diane Leg Lohan.

She was the only woman partner at Skidmore. I think she was the first woman partner in the firm.

[00:14:30] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:14:30] Speaker C: And I was one of, I believe, four women arch, four female architects in the whole studio of 50. And she was an amazing. And when you talk about mentor I mean, she was just an amazing person. First of all, the projects in the studio were fantastic. And I could go on and on about, you know, my first project, which maybe I'll get back to in a moment. But she also really kept an eye on us and in lots of different ways. I remember working, you know, you do a lot of after hours work when you're an architect. Of course, nine to five, doesn't matter, you're there till eight or whatever.

And she'd be right there with us and we'd be chatting about things. And I remember she was, you know, again, she would just talk about her life and you know, you just had this great opportunity to get to know someone who was at that time married to Mies van der Rohe's grandson and the first woman partner of the largest firm in the world. She also had us over at her home.

[00:15:36] Speaker B: Wow.

[00:15:36] Speaker C: She would bring, had the four of us who were women, she had us over at our home. It was really quite a thing. She kept an eye on us and made sure that she knew us and we knew her and we knew each other.

You know, that was special.

But also, as I said, in her studio, there were some amazing projects and I got to work on, you know, lots of times as a young architect, you get kind of thrown on project to project or you start on a day when you're working on a project that's almost finished or, you know, you never really get to see that end to end. Well, I had, you know, again, the good fortune of laying landing in the office and being able to be on a project from the very beginning, all the way to construction.

And it was a project actually. Again, I was working in Chicago, but the project was in New York and it was 875 Third Avenue.

[00:16:40] Speaker A: So who was the developer on that project?

[00:16:43] Speaker C: It actually was a family called the Gladstones and it was a New York residential estate family. You know, again, I'm way, way, way down the chain, so sure, you know, if I met them once, maybe, but the fact of, you know, just being on a project of that importance at a site like that, which is not far from, as we used to call City Court Tower. It's across the street from the Lipstick Building. Yes, two blocks, three blocks.

[00:17:11] Speaker A: Phenomenal location.

[00:17:13] Speaker C: I mean, just kind of an amazing location to be, you know, kind of have your first project.

[00:17:19] Speaker A: You're 21 years old listening to all this.

[00:17:21] Speaker C: So I'm the, you know, ultimate fly on the wall who happens to be part of the team who just sees, you know, commercial, real Estate in all of its glory at its best, and what was possible.

And I think it was that experience where I started to think about, wow, there's this other player kind of to Victor's story. There's this other player on the other side of the table known as the developer, client. And the client.

[00:17:50] Speaker D: Right.

[00:17:51] Speaker C: And that interest and that driver is like a major overlay on what is going to get built and how things get done in architecture, which we'll call the built environment.

And I think it was those experiences, experiences in particular at SOM where I was, I saw the role of the developer and I saw the role and the influence of real estate and was very, very interested and very curious about the fact that if you really wanted to shape buildings, that side of the table was going to be really important to be in that seat, or at least to experience what it's like to be in that seat. So I did my MBA and I ended up getting a job at Olympia and York.

[00:18:46] Speaker D: Oh, yes.

[00:18:47] Speaker C: Again, sort of.

And, you know, getting the opportunity to work with them. In the 80s, of course, that was sort of their heyday. They were the largest developer on the planet.

[00:19:00] Speaker A: Were you in New York for that, working for them?

[00:19:02] Speaker C: I was actually in Los Angeles, in la.

[00:19:04] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:19:05] Speaker C: The project was with the Chrysler Corporation in Detroit.

[00:19:10] Speaker A: Really?

[00:19:10] Speaker C: It was, you know, and again, that's my hometown. Oh, interesting. Well, you know, the Chrysler Technology Center. Right. Which was, you know, kind of this new campus.

[00:19:20] Speaker A: It's in Troy.

[00:19:21] Speaker C: They were building.

[00:19:22] Speaker D: Yeah.

[00:19:23] Speaker C: And the.

And Olympia, New York, basically had a land lease for the adjacent parcel. And we're going to build, I guess it was about 2 million feet of office space for suppliers for, you know, the partners. We know that 90% of a car is made by someone else, of course. And so it's those business relationships that you've really got to solidify to be able to deliver your cars. And the whole point of the technology center was to speed up the cycle, but we were kind of getting our butts kicked by the Japanese automakers at that point. And it was because they could turn, you know, from my concept to, you know, getting out on Six Sigma. Right. The whole Six Sigma. So, yeah, Chrysler was really determined to change that life cycle from idea to getting it on the road.

Having the adjacent supplier was this.

[00:20:19] Speaker A: After Iacocca was chairman or.

[00:20:21] Speaker C: Well, I'll get to that. I actually.

I mean, speaking of.

Right. You know, so a great, incredible man. I work with Marvin Richmond, who still is around today. Incredible man. He was a genius. You know, he had been involved in creating Water Tower Place in Chicago. He was involved with that project and he led O and Y Urban Los Angeles and which, you know, and did the deal on the Detroit project with Chrysler.

You know, we would fly to Detroit and in one, you know, one of these situations, again, I'm the fly on the wall. I'm the, you know, junior, junior person on the team.

And I'm in a room like this, you know, 8 person conference room, 10 person conference room adjacent to Lee Iacocca's office.

Lee Iacocca is in the meeting. Gerald Greenwald is in the meeting. My boss and one or two other people.

[00:21:23] Speaker A: Wow.

[00:21:23] Speaker C: And you know about the deal, right?

What a moment. I mean, you know, I don't think I said two words, but it was incredible being there in that sort of confluence of moments.

You know, I won't even talk about the crash or the ridiculous kind of run up of interest rates and deal going on hold and all of that that happened afterwards.

And of course Olympia, New York by the time we got to 1990 was just really kind of having challenges.

But what an incredible experience, kind of seeing and being involved. I mean the things I was involved with were really looking at the overall doing really all of the project schedules, being involved in kind of every piece in one way or another, really looking at what was going on with the potential tenants in the building, but also being exposed to of course these, the pro formas that started to get harder and harder to make work with this was double digit interest rates we were in. Everything was sort of coming to a crescendo.

So you know, I made a decision at that point, do I stay in real estate, work for a smaller developer, do you know, kind of these one off buildings? I mean after you sort of taste the, I mean O and Y had this really strong belief they created markets and that certainly was true when you looked at most of the projects they had done. That wasn't the situation with most developers who are chasing markets or trying to get there when you know at the right time. So you have this opportunity to be involved in the creative process in many different ways on any given day when you're at work.

And I love that energy. I also though, in going back into architecture and design, I wanted to be in roles where I could really bring what I understood about as Victor talked about what's on the mind of the other person so that we could elevate what we do, that we could bring to also think about the community, to also think about the tenants and their experiences in different ways. That as you said, ultimately studying those impacts through research and then really helping to lead a practice that really tries to bring together the experience of users, the parameters of realities around the economics, the long view of the city and all in a well managed and great experience for all those who are involved. And that's really what I set out to do when I ran the D.C. office of Gensler and we started to build a lot of these ideas into our projects, whether the Discovery Headquarters or any number of other projects that we did around here.

And then in 2005, Art Gensler asked Andy Cohen and myself and his son at that time to be the co leaders of Gensler.

And that was kind of this more way macro scale, international. Yeah, and the global scale as well.

Wow.

[00:24:53] Speaker A: Okay.

So Victor, as Deputy Mayor, your team successfully oversaw transformative projects in D.C. like City Center, D.C. the Wharf and Union Market.

How did these types of development projects help deliver critical long term revenue surpluses to the city?

[00:25:11] Speaker D: Well, well, first of all, John, you know it is, I find that most people don't understand or even people who work in government don't have clarity that it is actually a business.

It's a different kind of business with different objectives, with different outcomes. And any business has to be fueled by funding. You have to have some kind of realistic view that there is going to be a cash flow. You don't have a. I always tell, you know, Diane was talking about the interest rates and by the way, you can imagine us having conversations about this, you know, both working in different parts of the process and how much I got from her that she shared with me.

And then how do you take that and put it into your daily work on the government side? Because I was working on the government side, she was doing a lot of this. And my view as a deputy mayor and, and the projects that we had, I had been on Wall street and I'd worked in private equity, on Wall street, in real estate. So I knew what a non performing asset was. As a matter of fact, what we used to do is we used to find non performing assets and we would make them perform by retenanting, by renovating, by redeveloping essentially in markets around the country. That was my job. Raise money, deploy the money, get returns, pay your investors. That was the job. And what I understood about, I was saying this earlier, to me it was the city as a business and you need cash flows to fund services, to fund great schools, to fund affordable housing projects that you may want to do, fund police, fund fire.

There has to be A flow of funds. And when I came to. It's so interesting. When I came to D.C. i did not know the mayor. Mayor Gray, who at that time was. Had just been elected, and I had just. I was watching television. I remember we were watching television that evening. He was. It was this big celebration. And next day, he called me out of the blue, and I was like.

I thought it was a crank call.

I said, somebody, he's on the other line. He said, this is Mayor Gray. And I'm going, like, mayor Gray? You mean like the guy who just got sworn in the office? And he said, yeah. And I go, how did you get my phone? And he said, listen, a good friend of mine told me that if I wanted to transform the city, that I should talk to you. I said, you know, right now, I'm not that interested in working in the government again. I'm working in management consulting. I have offices around the country. I'm really not interested in working the public sector.

Before that, I was Secretary of Housing for the state of Maryland. Talk about a difficult job. God bless the person that does that job. It's very, very hard because you're trying to house people who don't have the means, and so performance is even harder to make work. Anyway, I was not really interested, but he.

He said, listen, let's just have a conversation. So I went to meet with him, and I was taken with his vision. He said, I want to transform this city.

I said, there were three cranes up in the whole city at that time. It was 2011. It was January 2011. There was no money. There was no equity. There was no mez debt. Mez debt was priced through the roof.

There was no basic construction loan. No one wanted to do a construction loan. Everybody was out of the game. It was like, no one was a tough time. Really tough time. And I asked him, I said, okay, so you want to do this, and I can help you do this, because I had reviewed the portfolio of the city and what was in the deputy mayor's office, and he wanted me to be deputy mayor of Economic Development. You know, I took the cut and pay, you know, took the job, you know, went in there, and, boy, what a mess it was. And what I mean by a mess is that nothing was organized. There was. You talk to one person, they'd say there were three projects in office. You talk to another person, they say there were 30 projects in office. Talk to another person, 15.

What I did is I got all my leaders in a room. By the way, deputy mayor's office in D.C. is an extraordinary position.

[00:28:58] Speaker C: There are.

[00:28:59] Speaker D: When I was. When I had the job was 1300 employees that rolled up to deputy mayor. There were 12 agencies, and they ranged from small business development to real estate development. It was a broad, and it's probably even more broad now. But the point is, how do you make that productive? And one thing that I had learned from the chairman of my department at MIT, Dr. Larry Susskind, he was a brilliant negotiator. And what I learned from him is that you really have to listen to people and you really have to find out where is the clearest thing that quote, unquote, true. Got to get the clearest truth if you're going to overcome obstacles, because that's all there were. There were obstacles, there were financial obstacles, there were community obstacles, nothing but obstacles.

So he taught us that. So City center was the first one that we took hold of. And City center needed funding. And Heinz, which was the developer, was well along in their process, but they had not landed on the equity that they needed to develop the project.

So we actually sat down with the people who were running Qatar Dr. Which was a massive development fund. 65 billion for existing assets, 65 billion for development.

We convinced these guys to invest 750 million in city center. And construction started about eight weeks after I joined.

And that was the first project that I put in front of the mayor. But when I did it, he paused. He said, hang on a minute. We need to do things in Ward 7 and 8. And my point was, you can never get to Ward 7 and 8 with Financial Services support if you don't do this project first, because this will produce the revenue.

And he said, okay. And we did it. We did the Wharf. We did Shops of the Dakotas, which had been around for about 30 years. That's where the Costco is. That's where the shopping center is. We did, obviously, Union Market. And the last one I did as I left was the Wharf. And I had promised Monty Hoffman that we would break ground on the Wharf before I left. We broke ground 90 days before I left.

And he was delighted. But the point is, all of those projects generated so much revenue. We had run pro formas on these projects, not performers from the side of the investor. We ran them from the side of the city. We actually did impact analyses.

We took this thing called the resource allocation model. I'm probably talking too much right now, but we took this model and basically used this model to predict how much revenue would come to the city. We did that in cooperation with the CFO and that. And what ended up happening is City center became the number one tax producer in the District of Columbia. And right now the Wharf is the number one tax producer. So from 2011 to 2014, we were able to produce 87 projects. And all of these projects were about 7.5 billion in total investment.

[00:31:48] Speaker A: That's fair.

[00:31:49] Speaker D: And we attracted the capital starting with Qatar. And we used Qatar to get in front of other sovereign funds. So we approached the Norwegian sovereign fund. After that we were anybody who had a lot, we went to China at that time, China was really open. And we actually brought a billionaire to Monty Hoffman to look at his project. And the guy said, I'd like to buy the whole thing. And Monty looked at me after he left.

That's not going to happen. And it didn't. Monty was right. But it was trying to get capital because the problem was a capital problem. So we were trying to cap up these projects because they would generate the revenue, ended up creating a billion dollar surplus for the city. And they ran that surplus until about two years ago. So the reality was we didn't forget the plot and we made these projects happen. But we had to help the other side of the table. We had to help them attract capital. And we just used our resources in tandem with theirs to get there.

[00:32:41] Speaker A: There's a big message for people listening right there. So listen to the other side of the table when you're making deals. Got to. Yeah, you have to. That's awesome.

Having held high level executive roles across Multiple jurisdictions, Maryland, D.C. prince George's County, Arlington and Fairfax, how crucial is embracing regional collaboration for tackling systemic issues like transportation infrastructure and the critical affordable housing? As you talked in needs in the Northern Virginia DMV area?

[00:33:14] Speaker D: Well, you know, it's like anything that you may, that you may perceive in terms of your profession. We often define our professions by the way that we are some job description that we have or some idea in our mind of the job description. And with government positions, you are almost defined by the boundaries of that city. You're deputy mayor of D.C. your job is be a deputy mayor of D.C. you're secretary of Housing for the state of Mary. You're Secretary of Housing for the state of Maryland. You're, you know, you're in Arlington, you're Arlington's economic development director in Fairfax. No matter where it is, when you're in government, it's really defined by those boundaries. But what has happened, and I would say that this has happened really in the last. It's been an arc over the last 30 years we've moved toward regionalism. That is that arc. You can't stop it because there's no way that our economy operates in these boundaries. You know, Arlington was the smallest self governed county in the United States, 24.6 miles. And it won the largest economic development deal in the world, which was the Amazon Institute headquarters. So how do you do that? Well, we never talked about Arlington. We always talked about the region. When we talked about the labor market, we Talked about the 3 million people in the labor market, not the 122,000 in Arlington. You know, though they were very smart. You know, educational attainment 73%. You know, Mass.

[00:34:36] Speaker A: Well, it helped to have the Pentagon there.

[00:34:38] Speaker D: Yes, it did.

[00:34:39] Speaker C: The reality.

[00:34:40] Speaker D: But the reality was this was the entire region.

[00:34:42] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:34:43] Speaker D: Set of assets that you went after. We didn't just talk about the universities that were located in Arlington. We talked about the university, the 60 universities across the region with 400,000 enrolled, graduating 90,000 a year. We look, this is a, we talk about it as a, as a talent factory and this same with transportation.

The roads don't listen. If you have a four lane road going into a two lane road from your jurisdiction to another jurisdiction, what do you have? You have a bottleneck that you create a mess. Really smart, right?

[00:35:12] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:35:12] Speaker D: So this whole regionalism I think is a, is an arc that we can't stop. And I think we need to lean into it because what it does was it really gives us greater strength. It really is really why Arlington really landed Amazon. It was because of everybody around Arlington. It wasn't Arlington. It was all the resources in the entire region. And then those intellectual resources, those are financial resources. The airports, we had the BWI airport in our application right along with the NY airports. I mean we talk because that's airport infrastructure.

So the reality is this regional view today, I would say today, maybe 30 years ago, not so much today. I don't think you can really compete nationally or globally if you don't have that regional cooperation.

[00:36:01] Speaker A: Well, you, you anticipated my next question, so I'm going to keep going. Securing Amazon's HU2 involved attracting $4 billion in private capital and linking the relocation to educational goals via $1 billion talent pipeline investment.

Why was centering the proposal around talent supply and educational infrastructure crucial to winning the deal rather than solely competing on massive financial incentives?

[00:36:32] Speaker D: So Stephen Murray was the president and CEO of Fairfax Economic. I'm sorry, of Virginia Economic Development Partnership at the time. And Stephen had come out of the education field into, into economic development. He had a PhD from Wharton. He had a master's in engineering from Louisiana State University. This guy is so smart. But when we talked, we met, when we met, we were at that time just closing the Nestle deal. And I had a conversation with him about that deal. And I said, you know, one of the reasons we were able to get this is that we worked with the 15 business schools in the region and brought them and whatever dean would come to the table to talk to their chief talent officer. I said, and that we felt like that was important in swinging the deal. And he said, you know, Victor, he said, you've got something there. He said, this is what, this is really the challenge going forward. And he really helped me see more clearly that that wasn't just a one off, that was like the future. So when the Amazon deal rolled up, which was not, that was like six or seven months later, the Amazon deal proposal came out and we saw it and I called him up and I said, you know, Stephen, we can't buy this deal. I said, there's no way. Virginia, Virginia would never put the kind of money into this deal that other states will. I mean, states offered 8 billion, cities offered billions.

That was not going to happen in the state of Virginia. I said, and by the way, I don't know if that's what they're looking for. So when we met with them, we listened to them, he met with them, our team met with them, we met with them together, we met with them separately.

[00:38:04] Speaker C: We.

[00:38:04] Speaker D: But we were all hearing the same thing. This theme of education, this theme of needing talent and how the talent issue became an issue in the Seattle Redmond market. And they were looking for that as a solution. So they never said that is exactly what they wanted, but we kind of, we heard it. And Stephen really came up with this idea. He said, victor, I think I could get the state to put like a billion dollars behind education. I'm going. Like I said, Stephen, if you could do that, this deal is going to happen here, it's going to happen in Virginia, it's going to happen. And he convinced them. He convinced the legislature, he convinced his board to pursue, he convinced the governor and then offered it to all the universities.

Two universities stepped up, Virginia Tech and George Mason. And originally George Mason was going to be down, Virginia Tech was going to be downstate.

We had to convince them to be upstate. As a matter of fact, I would say Stephanie Landrum, who was running economic development for Alexander at that time, she's the one that really convinced them that it was the place to be because of proximity to where we were proposing Amazon HQ2. It really dovetailed with what JBG Smith was doing and so everything was aligned and, and, but the thing that we realized very clearly is that talent from then on would be the currency of economic development.

[00:39:31] Speaker A: So I have to share with listeners to also listen to my interview with Matt Kelly of JBG Smith and with Evan Reagan Levine most recently, who is the strategy chief Strategy Officer who is redesigning and re configuring National Landing, which is now the campus for HQ2. So I'll stop with that. Advertisement Beyond a skilled workforce, what unique factors allow Fairfax County, Virginia's largest economy, to attract and retain major operations for tech giants? Particularly considering Northern Virginia has six times the data center capacity of Silicon Valley and the second highest number of AI openings nationally?

[00:40:16] Speaker D: Well, we have been very fortunate. Fairfax has benefited just like Arlington has benefited just like D.C. or Princeton. We all benefit from all these resources in the region. These resources in the region are so powerful. But it's how do you package those for the company's opportunity? And that's what we really focus on in our, in our county. We really focus on trying to meet the needs of the company, even if they go outside of our boundaries. I'll just give you one example. We have this thing called the Digital Hub. We started it five and a half years ago and we did it to provide talent to our companies. That was really why we started it. And then we started it right at Covid April 2020, we opened the website. We had about 15 universities on there. We had something like 3,000 positions advertised, maybe 30 companies. Today we have 7,500 companies on that digital website. We, we currently are marketing over 48,000 positions with our companies. We have 100 universities that we work with, 40 of them historically black colleges. We have really transformed what economic development means to our, really, to us in the county, but also to our region and our companies.

And I said it's the currency of economic development. Now if you have the knowledge workers, you can attract the companies. Because the companies and by the way, I think is a symbiotic relationship because once you win one of these companies, if you position it right, you attract more. And that's really kind of what we work at. We work at, if we get, if we get one company in a new industry and we see that industry growing faster than others, we pour our resources and we have, we have retrained people to work in different industries just so that we could catch the wave.

[00:41:55] Speaker A: So Diane, you worked For a major real estate developer for three years, Olympia, N.Y.

gaining a more robust understanding of the connectivity between the many disciplines.

What is the primary lesson from a developer's perspective that you urge young architects and planners to adopt when engaging with clients?

[00:42:16] Speaker C: Wow, great. Great question.

You know, I think there's so many pieces. One, you know, we talk about sides of the table. We're all on the same team.

And I think that's number one, is that, you know, yes, there's different accountabilities, responsibilities, interests, if you will, but at the end of the day, it's one team.

And, you know, so that's. That's one piece of. It is, you know, there's many. As Victor said, all these projects and things we're involved with in the built environment in particular, they're complicated and everything from, you know, the financial part, the codes and the regulatory environment, to the ownership and their aspirations to, in many cases, tenants. And then you have this thing called time, which, you know, again, don't control.

[00:43:13] Speaker D: This thing called time.

[00:43:15] Speaker A: I love it.

[00:43:19] Speaker C: And the fact of sort of the window of opportunity opens and closes so quickly these days, I think faster than ever. Where can. And time matters a lot when we talk about design. So I'll maybe talk about that in a moment. But I think the recognition of the fact that everyone has an assessment central part in this, you know, this overall ecosystem.

But also I would say as a person who'd been, you know, creative and an architect and involved in creating the product, I'll use the real estate term, the product versus the building that, you know, the things. Sometimes architects, and I'm not, you know, saying this to, you know, but just not understanding the other side of the table, they think that, wow, you know, they want to build this building for X amount of dollars. That's the budget. But if they see what it could be if they added 10% more, 15% more, they'll be so excited about that that they'll find the money to do that other thing, that 15% additional cost, because it's so great.

I don't think often architects realize how there isn't a 15% more out there that a developer has the ability to just go get because they love, you know, a great idea and that, you know, the budget and those. Those parameters are just like any other design parameter, that it's the constraints that create the innovation to lean into those constraints, whether it's a crazy site or it's some regulatory envelope that is complicated, or it's the timeline, the budget, et cetera. Et cetera. But find innovation in that reality, as Victor was saying, find the truth in all of those spaces and then innovate through that. And I've seen projects and been involved in projects where we were able to execute in those difficult parameters and create an innovative project that frankly set a standard.

I'll talk about when I did the call center for Amtrak, which there could not be a more complicated thing to do. One, you have a client who is quasi private, quasi government.

So there was a point in time where there was a configuration of the workstations that was going to be different from anything they'd ever done before. But we had proven this is what was needed to maximize the efficiency of the people who were working there.

It literally took a vote by Congress, the Congress of the United States, to actually be able to buy those types of workstations for the people who were working in that call center. I mean, there were constraints on every level.

And we were able to prove through research and study that this was going to allow for greater efficiency, less absenteeism.

And we were. And after the fact, it was proven.

The data of. Because when you're in a call center, everything is recorded, by the way. So they. And I still have the documentation of the increased number of calls that the people working in the call center were able to take in any given day. The lower absenteeism in that facility. And actually it was. That facility. Facility was ranked the number one call center in the world. Wow. At the time.

[00:47:19] Speaker D: And where is it located?

[00:47:21] Speaker C: Riverside, California.

[00:47:23] Speaker A: Really?

[00:47:24] Speaker C: Yes.

But I use that as just an example of one. You know, call centers are one of the.

You know, it's not a high budget project. Right.

You have, again, regulatory layers that are around unions that are there to the government itself, constraining everything.

And even where it was located had to be within a location that was the minimum cost for phone calls, because, again, the distance from certain utility lines mattered in a call center that was based on telecom. So all of these things.

But at the end of the day, not challenging those realities, but looking at how do we maximize the one thing that needs to be focused on here, which was the people and how they were able to do their job.

And I use that example not only as something I learned and that I feel like in design, to not suggest things that are outside of the reach of your client, but to suggest things that's. Victor said that double down on what you're hearing from your client, which in this case, when I was working with Amtrak, was the people who work there.

And that has been a theme for me as I've focused more and more of my career on workplaces.

And whether it's the full building and the interior or just the workspace itself, at the end of the day, the value comes from the value received by the people that work there.

I don't care if it's that 875 Third Avenue project I worked on or the call center in Riverside. The real metric is how value is, you know, how value arrives for the person who's there working.

[00:49:27] Speaker A: Do you ever script the idea of a day for a worker in your design process? So as you're, you know, you get up in the morning and you're going to work. And what's the experience like when you walk in the building and all that? I mean, does that come into the design process at all?

[00:49:43] Speaker C: Absolutely. That's how you do it. You really have to have empathy for the people that arrive at that door or drive into that parking structure. How far?

[00:49:54] Speaker A: Or shop at that shopping center.

[00:49:56] Speaker C: That shopping center center. You know, bribe for sporting events at a new state.

I mean, we do probably more airports than any other firm in the world. In fact, I was just at the grand opening of the new Pittsburgh airport on Friday evening, and, man, that is a spectacular project. I mean, a huge team. Gensler, the lead architect, along with hdr, the engineering firm, you know, Burl Happel was part of it. So many great.

[00:50:25] Speaker A: Was that a redevelopment or was that a new site?

[00:50:28] Speaker C: Brand new site. Really incredible story. And I, you know, I don't. I won't do it justice, but, you know, the Pittsburgh airport was the hub for US Air.

And, you know, ultimately, we know US Air doesn't exist anymore. It was a hub location.

And for years, Pittsburgh has kind of been saddled with an airport that was designed for one purpose, and that purpose hasn't been there for 10 years plus.

And so an entire journey of we want to, you know, that was for people traveling through Pittsburgh coming. You know, that's what a hub is. You stop and go somewhere else, right? Well, we want an airport that's for Pittsburgh and for people who live in Pittsburgh and this is where they live, and this is, you know, where they embarked from.

And that was really the whole focus of the project.

[00:51:21] Speaker A: So Gensler's research emphasizes making the office a destination, not an obligation.

What fundamental design principle ensures that the built environment enhances the human experience and fosters the visceral experiences people now demand, regardless of project scale? This is a follow on, basically.

[00:51:42] Speaker C: Yeah, you know, this is the whole point of, you know, following what is going on in the workplace was really the reason behind starting our research institute 20 years ago. You know, really trying to find that link between how does the workplace impact someone's productivity and thereby impacting the economic performance of the company.

And so we really sought to bring some concrete metrics to that question. I think so many of our clients, and Gensler celebrates its 60th year. This year and through our entire history, clients always talk about in an anecdotal way, wow, my company is performing better. My people are more excited to come to work, and there's much more clients collaboration or there's much more this or that.

So when we look at, you know, kind of the question of what is a workplace that's a destination and not an obligation? And a lot of that language comes out of what we all just went through, which, you know, during COVID of course, we were all kind of, you know, required to work alone and at home and all of that. And then, as you know, vaccines and safety was established, you know, moving back into that workplace. And as you know, we all know, there was a lot of choice, there was a lot of individual decision making that really created how fast or how slow a company was going to move into being in person, if at all.

And the fact we started seeing that people wanted to go back into that office environment, but not the old office environment, not what they left, but something that met their needs more that, you know, during COVID I think people realized the value of quiet, the value of being able to focus and not be distracted.

And their workplaces pre Covid, in many cases, didn't have enough variety of different kinds of spaces to be able to have the quiet time if they wanted it, have the collaborative time if they wanted it, but to have enough different places to be able to do that.

So, you know, when we look at the design of the workplace today, that people are looking for, that companies are looking for, that they know is what motivates their folks to want to do that commute and be there. It's one that offers, again, a wider variety of experiences and recognizing. And we talk about different people, frankly, have different needs. We can call it neurodiversity in some settings, and we use that word a lot when we're talking about folks that in fact, we have a quiet area on our third floor. Lots of companies now have a few quite quiet zones. There are people that will be there 100% of the time because that's, you know, kind of the mode and the way the environment that is going to maximize their capabilities.

But most people, it's a mixture. You know, I've got to do a ton of heads down work this afternoon. I don't want to be distracted. I might go to that quiet zone.

Others, you know, they like the busyness of the energy around them. So they will be in that space that might be right adjacent to a cafe area or maybe in the cafe.

Most people, again, it's probably that happy medium that is allowing for that overhearing of team members that are working on things that they have in common. So there's this ambient learning and staying up to speed and that someone can kind of know, help with either oversight or mentoring or answering a question and you're not having to run around and look for them.

So, you know, again, one size does not fit all.

It takes a really, I would say more focus today, more energy in really understanding what makes that company tick, what makes that organization tick. You know, we use a tool that we've developed called the Workplace Performance Index, the wpi, to really get at that issue of, you know, how much and how many of all these different kinds of spaces and what is going to be the right mix for the people.

But I think the biggest thing we got out of COVID was, you know, and we talked about it before, listening, you know, listening to people that work in your organization that, you know, there's incredible, incredible wisdom that will come from that. You won't build spaces where you're wondering why does no one use that space that we just built?

That might have been great in that magazine that you were reading and that other company was using, but it's not your organization. And so really doing the homework and in listening to people is the first step.

[00:56:56] Speaker A: It's interesting. The definition of a workplace has changed so much.

So I've interviewed Toby Pezuto recently, last year, and he said you can't believe the transition of apartment buildings from before the pandemic to today.

So in essence, he said, we turned into a hotel operator as opposed to an apartment owner because you have 24, 7 activity in the lobbies that you never had before.

So in essence, there's another design question. How do you design for, you know, much more activity in an apartment setting than you ever had before. So it's a. There's another different. And that in essence becomes a workplace for a lot of people.

[00:57:39] Speaker C: Absolutely.

[00:57:40] Speaker A: Oh yeah, it's really interesting.

[00:57:42] Speaker C: You know, we. It's such a great point and knows Toby pretty well. I think you're absolutely right. This kind of Work everywhere is an interesting point, but it also means we need workplaces everywhere. We need a work, co working or whatever you want to call it, library spaces in our multifamily housing developments. In fact, you know, people see that as an essential amenity that there are these kinds of alternatives, spaces that are there. It makes all the difference in the world. We're seeing that also in office buildings, that this amenitization is, you know, it's a requirement. It's not a. If you want to attract the class A premium tenants, they, you know, they want to build their space, but they don't necessarily also want to build that huge conference space that they only use, use once a quarter.

Well, those kinds of spaces are now part of the amenity package in the premium buildings. And frankly, if you look at, you know, a full office, you know, a building of many, many tenants, that space is going to get used pretty regularly. But an individual law firm, you know, that would normally build one of these large conference centers now doesn't necessarily have to be build that in their space.

And they can devote their space to this whole variety of different, different places that their people are going to use on a more regular basis. And the same thing with whether it's, you know, F and B or coffee bars or those sorts of spaces get used, you know, again in office buildings and are part of the expectation. You know, of course there's a whole array of other kinds of spaces, whether it's the gym or, or some other kind of areas.

But this idea of the community, building community within our buildings, building community within your workspace, building community within the building and building community within the neighborhood, is much more of an intentional design challenge. And part of what we're doing now, especially with what we know from customers, you know, I think there was a lot taken for granted, Gee, that those kind of places are always going to be there. But I think we realize how important those places are and that we want to feel like we're part of communities kind of at every level in the lives that we live.

[01:00:15] Speaker A: That's great, Diane. Your off track is on track philosophy warns against the frog in the well phenomenon.

Knowing only one specialty, what practical steps can young commercial real estate professionals take to build a latticework of mental models, which is the refers to the speech that I sent you. I don't know if you had a chance to listen to it by intentionally crossing academic and professional silos.

[01:00:48] Speaker C: Yeah, I think it is absolutely essential to be careful about, you know, over specialization.

[01:01:00] Speaker A: Right.

[01:01:01] Speaker C: And whether it's just, you're more marketable and more flexible given, you know, the kinds of changes that can happen in the job market. Right. You have more skills to lean on. But the point that you're making, which is your own ability to think creatively and to be a problem solver, that you have more tools at your disposal. If you have experienced a variety of different disciplines and whether it's even the music and dance and art and engineering and in fact many people who are strong in math and science have a strong balance that they give their thinking through the creative arts. And whether one is part of the other, it probably is more one is the opposite of the other and kind of stretches your mind rather than just being so reductive. But I believe that very strongly. I mean, my career definitely went from lots of kind of work, architecture, you know, to interiors to real estate, back into architecture, going from sort of design and into kind of practice leadership. I guess in many ways I, you know, took risk in each of those. And I think that's the challenge is the risk you take when you try one thing versus another.

But I also believe that you are only going to do great work if you're interested in the work.

And so following your interests, following kind of the thing that is on that edge of the bell curve in your mind that keeps getting your interest, it's important to follow those things because you just don't know what door that's going to open for you. You that again makes you a very, very successful person because let's face it, great success is only going to happen but so often.

And part of that, and I think everyone has the potential, it's the willingness to take the risk.

[01:03:20] Speaker A: Also the other thing in my view of this multidisciplinary approach, perspective and how many different perspectives you bring to the table with that discipline, with understanding all these different things, you can see things from different angles, which to me is critical, I think.

[01:03:40] Speaker C: Absolutely, absolutely. I think it's also, I mean, you know, you haven't asked about it, but usually when I'm interviewed, there's always some bringing up of being a co sign CEO and what that's all about. And in many ways it's exactly that point of cross disciplines seen around corners, seeing beyond your own thinking. When you have a partner who's very different from you and that you have mutual respect and trust, that you get pulled into things you may never have thought of and you're pulling so into things they never have thought of and it creates again potential in your organization that goes beyond just the Thinking of one person.

And that's good for our organizations. As much as a wonderful CEO can be fantastic.

The world is changing too fast and.

[01:04:37] Speaker A: We all have blind spots, don't we?

[01:04:38] Speaker C: Right. That's just being human. Right?

[01:04:42] Speaker A: Absolutely.

Gensler's research found that high performing workplaces require a balance between collaboration and quiet zones. You've already talked about it. How does Workplace Performance Index help quantify and optimize this balance for clients transitioning to hybrid models?

[01:05:00] Speaker C: Yeah, just to kind of add a little bit, because we did talk about that. Look, we literally look at kind of not trying to change who your organization is, but how do you enhance what people, how people work, what they believe is, is going to unlock their greatest potential.

[01:05:21] Speaker A: What was the most difficult challenge to try to address in that framework?

[01:05:25] Speaker C: In that, you know, I think the hardest thing. There's so many hard parts of this.

You know, look, I think the biggest challenge in the, the transition from COVID to where we are today is courage, courage to do something different.

And frankly, I have seen a number of tenants in buildings, we're working with them and they're gun shy of taking enough space, so they take less because they know their board has heard about hybrid and all this sort of thing. So they believe the expectation is that they should take less space because of these kinds of factors. And look, nobody has a crystal ball. Maybe the whole organization is going to be working from home one day and there's always someone on every board that's like, wow, you guys have your heads in the space.

[01:06:25] Speaker A: So how do you sell more space?

[01:06:28] Speaker C: I think this is the challenge with all of, you know, all of the roles we have. I mean, you know, if you're the developer, you are seen as having, you know, self interest if you're trying to sell more space. Right. So, oh, that's negated. I think what is happening right now is that many tenants who have built space recently are realizing they're out of space already.

And so this kind of building in, in effect a future challenge that I think everyone thought, well, you know, it'll be something we can deal with. Then I think it's come up faster than most companies thought. They thought maybe this hybrid thing would just keep pushing the need down when in some ways growth and the fact. And I heard, I was at a dinner the other night and a woman from one of the financial institutions, she said, everybody we're hiring now is requiring that they have an office space.

[01:07:30] Speaker D: In.

[01:07:30] Speaker C: The facility, that they want space. They don't want to be considered hybrid. They don't want to be someone who doesn't have a dedicated space.

And this is what we're starting to see now. Like the tide is starting to turn. I think the financial services industry in general has been ahead of the curve on this.

But that where if you look at a lot of the data, it's been an interesting following of people who were looking for jobs that were hybrid or work from home, that's gone down dramatically. But now it's the demand for space in the office as one of the conditions.

[01:08:12] Speaker A: Have you found a CEO that sees your view and say, okay, we're going to take a chance, we're going to do something special here and build something that's extraordinary?

And in my view, what I've seen is the common area of buildings today has really been the leading edge of what's going on.

You know, you're, I walk into your space, you walk in and you've got this really open lobby and the staircase going up.

And I saw all these people congregating on the ground floor today because you have this special event going on. It's like, wow. You walk in, you just feel the energy as you walk in the building.

Now that would excite people. Oliver Carr, who's another interviewee of mine, there's a building in Bethesda called the Wilson. You walk in that space, it's just wow. This is an amazing physical setup. And he has gone out of his way to make common areas very special and buildings that he's been involved in developing.

Ray Ritchie developed a project here on Pennsylvania Avenue, not far from where we're sitting.

It's just an incredible project. His most recent development, Wilmer Hale, is the anchor tenant. He has a building inside the lobby, another building physically in the building, that's a structure inside the space. It's a spectacular spectacle, like three story lobby. You know, to me that's been the change to attract people back. It's like you walk in, you want to feel like you're in a special location.

[01:09:53] Speaker C: Absolutely.

[01:09:53] Speaker A: Maybe I'm overstating it, I don't know.

[01:09:56] Speaker C: So you tell me that's, that's exactly. That's the destination, not the obligation.

[01:10:02] Speaker A: So as global co chair, overseeing 6,000 plus people across 56 officers, how does Gensler's one firm, firm philosophy and collaborative leadership model, where one plus one equals five. That's an interesting calculation.

Ensure the vast network functions as a true integrator of ideas by leveraging a diversity of thinking?

[01:10:30] Speaker C: Yeah, well, we really believe strongly in collaboration. And look, Gensler didn't make that up. That's been a reality of any innovative company. Any company that is focused on the creative aspects of whether it's tech, whether it's design, whether it's advertising, whether it's any company that is, you know, frankly looking to stay ahead of their competition.

That it's about, you know, collaboration. It's about bringing teams, strong teams together, that where you have people who inspire each other, who are building off of each other's ideas. And that's what we've, you know, what we've built at Gensler. We're not an assembly line. We're not a cookie cutter kind of organization. We're, we're not trying to do the same white building over and over again. And people buy sort of a product.

We bring teams together, different folks on every team is different and the client is different. So it starts with that. You have a group of different people together, a client.

And it starts with these conversations about where do you want to be? What's your vision, what are your aspirations?

[01:11:49] Speaker A: I look at the calculation of one plus one equals five and I say, this isn't mathematics, this is chemistry.

[01:11:58] Speaker C: Love that.

[01:11:59] Speaker D: That's great.

[01:12:00] Speaker A: So I'll let you define exactly.

[01:12:01] Speaker C: I love that. I'm going to take that. Oh my gosh. It is chemistry and it is.

[01:12:07] Speaker A: I'll let you define that.

[01:12:09] Speaker C: That is chemistry. That's. We always talk about the secret sauce and that's our culture and that's the recipe. It's the unique chemistry of all those different elements with, you know, the, the pressure and the heat and the all of what's around it to innovate and to create the solutions. There's, you know, again, lots of different constraints. It's, you know, a site that is, got some topography issues or it's right on a busy street or it's got some interesting neighbors, or, you know, there's some toxic something that has been there 100 years ago. I mean, there's all kinds of things on every parameter.

[01:12:54] Speaker A: Victor, you currently sit on GMUs, George Mason University's Presidential Innovation Advisory Council.

How does PIAC guide the university in structuring its research and curriculum, such as the Institute of Digital Innovation, to meet the rapidly evolving talent demands of Northern Virginia Tech industries? It's a big question.

[01:13:18] Speaker D: You know, the leadership is everything, as you know, John, and this university has led in many different ways. It is the largest now public university in Virginia, the state of Virginia. It has over 40,000 enrolled. It is the numbers, by the way. It's grown when universities all across the country have shrank, and their graduation rate is like 80%. I mean, it's unbelievable in five years. So they're pulling them in and they're cranking them out. And in order to do that, though, you have to think differently. And I think that, you know, we thought about the campus itself as a physical location to bring together industry, academics to solve a real problem.

That was. That's kind of the concept, but actually doing it is very complicated. I worked for a city manager many years ago in Long Beach, Jim Hankler. And Jim Hankler, he had a vision for the port. The port was part of port. Long beach was part of the.

Part of the city. And he viewed the port as an essential part of the entire economy of the western region of the United States. That's how he looked at it. He didn't look at it as Long Beach Port needs to generate revenue to help Long Beach. He looked at it as. This is international trade.

We have to make this conduit work most efficiently. We need to be supporting the flow of containers. Because that.

That was becoming. And this is back then, that was becoming the mode by which people move goods. And that was an extraordinarily innovative thought. And then he said, but you know what? We have to get them to the railroad tracks to the north, which were in the central part of Los Angeles from Long Beach. But the highway system couldn't hold it. So they created a separate. Conceptually, they wanted to create a separate truckway. And actually, he left Long beach to design and build that.

So he was a constant innovator. So I watched him and how he worked.

And even Mayor Gray. Mayor Gray came into the city when it was running budget deficits, and they had spent down their reserves from a billion 250 to 750 million.

And the CFO was. The first lesson he gave me was that, you need to fix that. I go, I need to fix that? No, we need to fix that. And the mayor knew he needed to fix that, and he developed innovative ways to do that. And still providing 10,000 housing, affordable housing units, providing, you know, amenities that we all love. You know, the wharf and, you know, look at 14th Street, 8th Street. All these places happen because of innovative thinking. That's the kind of innovative leadership that you need to make something like this work, because you can't be afraid to bring together people who don't necessarily view the world the same. You know, the. You know, the governor just opened up the energy center at.

At this. At this fused location. They are working on small modular reactors, SMRs why? Because we have an energy problem right now that we need to solve in a different way. And it's the only simulator in the country that is on a campus. And these students are going to learn how. And it was built by a private sector company that has been licensed for small modular reactors. So SMRs. So this is a place where these people are going to be trained and they will be able to go into a facility and in a very short time be productive. And I think that that's the whole thing. How do you bring together these.

You know, in a way, when you think about it, small nuclear, small modular reactors are not really new. It's just they're being used in a new way. You know, every, every nuclear submarine has two, every aircraft carrier has two. So it's not like we haven't been using them. It's just we want to use them in a different way now. And I think that that's the kind of understanding that you have to bring, you know, into the process and again, not be afraid of doing things differently. Because realize this, that campus is not in Fairfax county, it's in Arlington County.

So I'm actually working really in the interest, it looks like, for Arlington county, but it's not, it's actually fair for the entire regional economy. It goes back to this thing of understanding that you need to be regionally collaborative in order to make things work for your county.

[01:17:42] Speaker A: Victor noted that very few companies have R and D programs that are strong enough to do that kind of work individually.

How is Fuse at Mason Square?

345,000 square foot innovation Center. That's big.

Designed to integrate academic deep research with industry to solve problems that single companies cannot.

[01:18:02] Speaker D: Yeah, well, you know, recently George Mason became an R1 university, which means that they have major research grants and this major research grant capability is being taken advantage of in that location in the Fuse Center. And I just mentioned energy, I mentioned the small, the SMRs. But they are also working on how do you innovate and improve existing systems. They're working with Dominion and other power providers in these innovations and, and the public money combined with the private money to solve a real problem is actually where the opportunity is. Because they're solving real problems. Industry is bringing them. This is our problem right now.

We need 40 megawatts in order to provide for the next 12 months to 18 months for the data center capacity that we're building.

We got a problem and we have to solve it quickly. And then where do you take that? You take it to people who are really really smart and some just academically trained and some that are trained in a practical way, they already have practical experience. But finding a place where you can combine them and they can work together, because there's no company, like you just mentioned it, that has enough money to solve these problems alone. If they were, they would have done it and they'd be selling the energy. That's not what's happening. These companies are now working together and this is a space, this is kind of neutral territory. View it that way. Think of it as neutral territory where, you know, Meta and Amazon and Google and all these companies that are brand name companies can come in with smaller companies because a lot of smaller companies are working in these facilities also and work together to solve a problem that actually will serve them all, will serve the entire industry. I think that's really the kind of the clever part of it.

[01:19:48] Speaker A: Given the growing national cybersecurity crisis and the influx of defense and aerospace companies, over 70 space industry firms in three years, how does Fairfax County Economic Development leverage Northern Virginia's massive pool of 65,000 plus veterans and regional initiatives like V3 and career fairs to fill the high demand cybersecurity and national security talent gap?

[01:20:15] Speaker D: We've been very fortunate that we have so many veterans transitioning out of Belvoir for Meijer Quantico.

There are massive transitions that happen every year in our state.

The good thing is that many of them are here and we can reach them. So we actually, as part of this digital hub that we created, we've actually staffed a veteran to work directly with, with the military bases and actually to have sit down classes with people coming out of the military, particularly people that may have cyber background or may have cloud background or have, you know, some kind of deep coding background. They're easy to play, the easier to place in our defense companies.

A lot of them have cleared status. When you have cleared status, you go up in the rank, secret, top secret, that is, that'll get you to the top of a lot of interview with piles if you have that kind of status. So our veterans are actually a resource, a natural resource that we can, you know, make part of our growing economy. And that's exactly what we've been doing. This V3 program, Virginia Values Veterans Program, for example, we have a person on our team that actually works with these companies first to get certified and then to help second to help them find the town. Because you have to really have someone available to counsel these, these veterans because often their resumes are written for the military environment. I move Tanks and guns and artillery. No, no, no. You were a logistical expert moving things just in time in order to meet critical deadlines. And that is, someone has to help them do that. This has been done one on one. We're trying to actually move this now to use artificial intelligence to do this. We just launched last week with all the regional players and artificial intelligence overlay over our digital hub, which will allow you to have your resume reviewed. You can have a conversation with the agent. You know, it's an artificial intelligence agent, but it's an agent nonetheless. And it'll help you improve your capability of landing a job if you're in transition. And this has become important, particularly since the changes in federal policies that have affected a lot of people who really are very talented. And what we're trying to do is guide them as quickly as possible back into employment because we need them taking care of their families. We need them being the strength of our economy. We don't need them to leave because actually, talent is our competitive edge right now.

[01:22:37] Speaker A: That's great.

Diane. Buildings account for 40% of all CO2 created as chair of the sustainability committee for Boston Properties. How does the message of design for radically changing world inform investment decisions specifically regarding adaptive reuse to save embodied carbon?

[01:23:01] Speaker C: Yeah, you know, two weeks ago I was in New York for New York Climate Week, which was, you know, again, an incredible event. And what was fascinating, I was on a panel with SAP and Amazon for Financial Times panel talking about commitments that large companies have made and, you know, what is happening now. You know, years pass and are you still on track to make those commitments? Good. And I think what was interesting, and I thought it was really enlightening, is that.

And, you know, we can talk about this at the real estate level as well. Well, but, you know, look, real estate is there to serve the economy. It's there to serve homeowners. It's there to serve, you know, again, the community in various ways. So what's going on with those folks will drive, ultimately, what is going on with real estate.