[00:00:09] Speaker A: Hi, I'm John Co and welcome to Icons of DC Area Real Estate, a one on one interview show highlighting the backgrounds and career trajectory of leading luminaries in the Washington, DC area real estate market. The purpose of the show is to highlight their backgrounds and their experiences and some interesting stories about their current business as well as their past, and to cite some things that you might take away both from educational standpoint as well as lessons learned in the industry and some amusing and sometimes interesting background stories. So I'm hoping that you will enjoy the show. Before I introduce my guest, I'd like to share that both this podcast and the community I started in 2021, called the Iconic Journey in CRe, is now part of a new nonprofit organization with that same name. The new company will offer opportunities for sponsorship to grow the community both in membership and in programs. It also allows you as listeners to show your appreciation for this podcast, which has delivered episodes twice monthly since August 2019 with a charitable contribution.

Transitioning the community and podcast into the nonprofit organization is underway. The community, which is open to commercial real estate professionals between the ages of 25 and 40 years old, is currently up to 65 members and growing. If you would like to learn more about either joining the community or contributing to the podcast, please reach out directly to me at John at Coenterprises coenterprases.com separately, my private company, Co enterprises, now will focus only on advisory work for early stage real estate firms and career counseling. If you have interest in learning more about its services, please review my

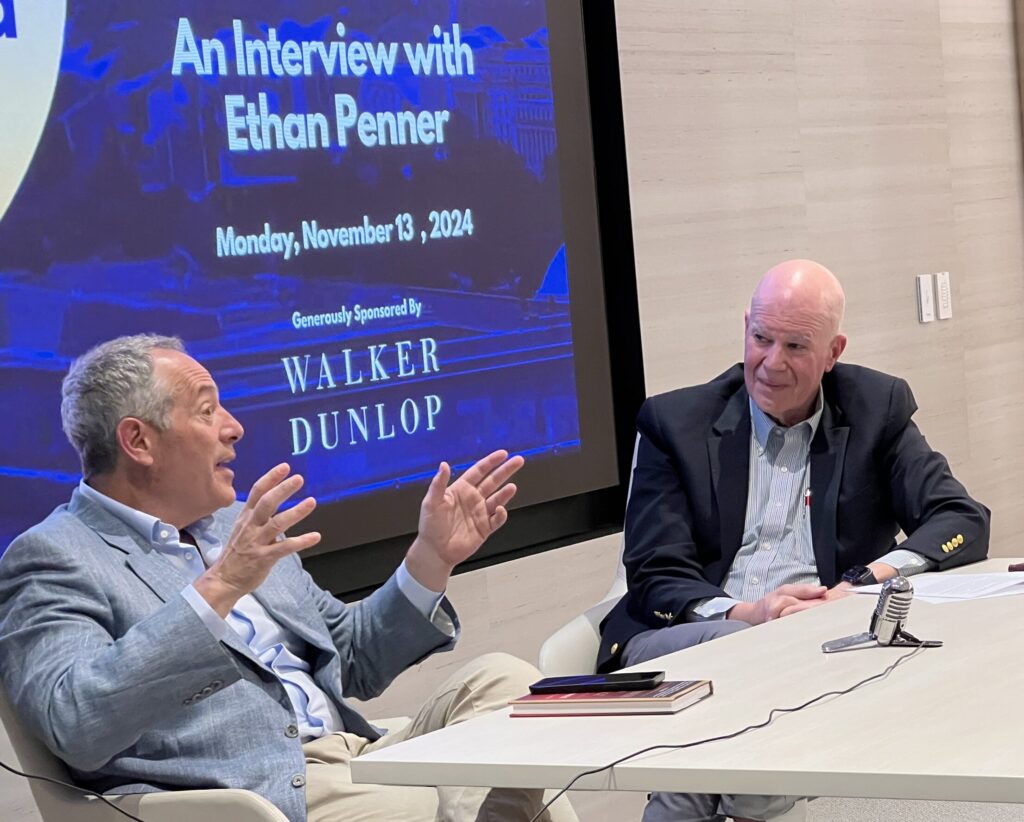

[email protected]. Thank you for listening. Thank you for joining me for another episode of Icons of DC area Real Estate. Actually, this is the 100th episode of the podcast and I am extraordinarily pleased to introduce my unusual and pioneering guest on this show. And that is Ethan Penner, who was the founder of the CMBS commercial mortgage backed security industry back in the early 1990s, and he has recently written a book called Greatness is a choice, which we talk quite a bit about in the conversation.

This interview was recorded live at the headquarters office of Walker and Dunlop in Bethesda in their beautiful space in front of an audience of members of the iconic journey, as well as a few of the team at Walker Dunlop.

We discuss his trajectory into the mortgage industry via his challenging upbringing in a divorced household, starting his career in the savings and loan industry, and then to investment banking with Drexel Burnham Morgan Stanley, and then the mirror securities, where he ended up starting the CMBS industry. After seeing the devastation of the early 1990s with the SNL crisis as well as the banking dearth of capital.

So his career after starting the CMBs just exploded because the market was just really needing capital. And he found a way to be a bridge from the bond market into the mortgage market with that vehicle. And so from about 19 92, 93 until 98, they were the top firm in the marketplace doing at Namira securities, doing tremendous volume. He was then let go for political reasons in 1998. And he talks about it and left the industry for several years, went to Hawai and he talks a little bit about that, meets his second wife and then emerges again in 2008 with CBRE and he talks about how he did that.

They funded him for a while and then he joined, started his own company shortly thereafter. About two to three years later, he had success with his own company, kind of opportunistic, investing more in the debt side. Of course, that's his experience and expertise. But he decided after a lot of contemplation and going back to his faith, to start compiling writings, which he then built into his current book called greatness is a choice. And he talks quite a bit about that. We talk about his philosophies. The book is divided up into chapters with titles that are very interesting, and I won't go into them here, but we talk about them in the conversation.

We talk a wide variety of subjects, including real estate, finance, interpersonal relationships with his family, his wife and his children, as well as his parents social issues in the markets today. His belief, believe it or not, in a 6th sense of who he is. And he talks a bit about that in relations to a herd mentality thought process in his book. So he's become quite a philosopher and he believes that we all have greatness in us if we choose to use it. So please enjoy this wide ranging conversation with Ethan Penner. So welcome to the icons of DC Area Real Estate podcast in front of a live audience today at Walker and Dunlop. I'm pleased to introduce Ethan Penner, CEO of Mosaic Real Estate Investors and author of greatness is a choice, his recently released book.

We will infuse his biography in this conversation.

We met each other over 25 years ago at the Mortgage Bankers conference in San Francisco.

[00:06:55] Speaker B: Thank God we look the same.

[00:06:58] Speaker A: When I'll never forget what you were wearing that night.

He had a headdress on, I think that was probably several feet tall, and a coat, which I would call the Technicolor dream coat that you had on that night.

[00:07:11] Speaker B: It was pink with black lines and I had just come from celebration of the chinese new year and that was my ox colors, apparently, because I'm a year of the ox, and I just flown in with some friends from Mexico for that party. And it was quite the party.

[00:07:31] Speaker A: So his company, Namura, at the time, had Santana and Crosby, stills and Nash back to back that evening. For 3000 of us in mortgage banking, it was a very special night, huge event, and only one of many that his company hosted over several years.

So, Ethan, since most of the audience is younger and may not understand the market cataclysm and reset of the late 1980s through the mid 1990s, perhaps share your career trajectory. Start at Drexel through Morgan Stanley to Jira through those times, and how you were fortunate enough to build the franchise.

[00:08:11] Speaker B: You did well, I think the word fortunate is definitely a very relevant word to use and you reference, I think I wrote a book, and there's a chapter dedicated to the concept of timing and good timing, which is another way of saying good fortune or good luck. And I think that anyone's success is always a combination of hard work and a little bit of intelligence, or maybe a lot, depending upon the person, but also good timing, good fortune, good luck. And mine was definitely a combination of those things. Hopefully some intelligence was in there, too, but definitely good timing, good luck, good fortune was there.

I came out of college, and it was a very challenging time in the early 1980s. It was a pretty deep recession. Interest rates were very, very high. As you remember, the ten year treasury was 1565. Okay, so when we think about high yields like we think of today, oh, my God, the tenure is at five.

It was 15.65 when I got out of college. And that tends to squash economic vibrancy pretty soundly. We think about today's fed trying to tame economic inflation with 5% tenure. You can imagine how tame an economy could get with 15% tenure. So I got out in that time, and I took the first and probably only job I was offered in finance, which was in the mortgage business at a savings loan. I was fortunate enough to kind of work my way quickly onto Wall Street. Wall street had just adopted mortgages as a business that they were interested in, and the trading of mortgages had just kind of started, really around the time I got out of school.

[00:10:05] Speaker A: So wasn't MBS was based on rmbs, right?

[00:10:08] Speaker B: So what we call RMBs was just called MBs, right. There was no r or c. It was just mortgage backed securities was a new thing.

[00:10:17] Speaker C: MBS.

[00:10:19] Speaker B: Fannie and Freddie were participating, and I kind of started on Wall street.

My first job was at Drexel as you suggest, John? I was trading non agency guaranteed. So credit risk intensive mortgages. I was the first class of traders ever on Wall street to make markets in credit risk instruments. And then me and people like me started to use structured finance techniques, which were very basic. Just taking a pool of loans and creating a senior 90% class and a junior 10% class, and getting the senior class rated by the rating agencies, typically aa, and selling those aa bonds to bond buyers. And I got lured away by Morgan Stanley, who wanted to get into that business, had not gotten into it yet. And I found myself running, starting from scratch and running, really, mortgage finance and mortgage trading for Morgan Stanley, not including Fannie's, Freddy's and Jenny's, at the age of 26, something like that. And I became the youngest principal in the history of the firm. And I love my career at Morgan Stanley. But then, as you point out, there was this incredible dislocation in commercial real estate. And it seemed obvious to me that the same securitization structured finance business that had been applied so successfully by people like me on Wall street to single family mortgages could be applied to commercial real estate and help solve the liquidity crisis that existed, which was. I don't think people today, just like people today, can imagine a ten year treasury at 15. I think it'd be also equally impossible to imagine not being able to get a mortgage at all. Okay? It didn't matter how great your property was, didn't matter the location, the occupancy, there were no lenders.

I'm telling you that in 1990, and you remember this, 1990, 1991, if you had a loan on this, let's say this beautiful office building that we're sitting in, and it was 100% occupied, and you had a 50% loan to value exposure at a ten cap, there were no lenders for you.

[00:12:41] Speaker A: Not only that, the lender. If you had a loan on it.

[00:12:44] Speaker B: No, they didn't want you to pay it off. No, they would not roll it at all. They might give you a six month extension, but they wanted no part of that loan, and there were no other lenders to turn to. And so it was a weird moment where an industry, perhaps one of the largest industries in the United States, everyone was facing bankruptcy and insolvency. And this 30 year old kid, me, kind of had this idea that securitization could be the solution to this industry's liquidity crisis.

No one else. Even though I wasn't the only one who came from this background, I guess I was the only one imbued with dreamer mentality.

I think that when you do something that's never been done before. So securitization had never been applied to commercial real estate before. And when you go to do something that no one's ever done before, everyone tells you, well, if it could have been done, wouldn't it have been done already? Like, why you? And I was like, oh, well, I don't know, but I'm doing it. My answer to that is, I don't know, but I'm doing it. Everyone's other, I think everyone else probably just kind of figured if it was doable, someone else would have done it, so why bother? I guess I don't know either. I'm dumber, more stubborn, more persistent, maybe. I believe in myself. I don't really know what it was, but I just kind of ran through all the obstacles of doubt that existed in, how did you get the rating agencies on board? That was tough. So I'll tell you.

Lately, because of my book, I'm doing a lot of speaking, podcasts, public speaking, and I enjoy very much when it's a real estate crowd and we could talk specifically about things like that. So how did I get the rating agencies to overcome what was a level ten fear of real estate that was pervasive in the world? Right?

[00:14:44] Speaker A: It was.

[00:14:45] Speaker B: And anyone like I left Morgan Stanley in order to pursue this opportunity. Why? Because real estate was the third rail of finance, and no one wanted to touch it because they feared losses, loss of job, loss of money. And Morgan Stanley was no different. And they said, listen, john Mack, who ran fixed income at the time and was my boss and ultimately ran the firm, said, we don't want any real estate exposure on our balance sheet at all. So if you want to leave and go do it, good luck, but you're not doing it here. And I said, well, I do want to leave. I do want to do it, so I'm leaving. And I left. How did I persuade the rating agencies? So I'm going to share a conversation with you and your audience.

I sat in the room with the head of one of the rating agencies who was structured finance, mortgage finance guy, and I just started to explain to him the logic that at some attachment point, there is great safety in the loan. And he said, okay, I agree with that philosophically. He said, but this gives you an idea of how bad things were. He goes, but if there's any office exposure, we're not rating it. There's no investment grade, none for office, none. So we happened to be sitting in two world financial center where Nomura was headquartered. And I said to him, ron, we're sitting in this building, and even now, in a very depressed valuation moment, what do you think this building is worth? Just pick a number. And I don't remember what he picked, but maybe it was 400 million. It was a big number because it's a beautiful, big building. Let's say 400 million. I said, fine.

If I had a $1 million first mortgage on this building, would it be rated investment grade? He goes, yeah, it'd be rated aaa. I said, well, there you go.

Now we know that you will, in fact, rate office investment grade. And it's just a question of the attachment. But he goes, yeah, I guess you're right.

[00:16:52] Speaker A: How much risk do you need?

[00:16:53] Speaker B: I said, so it's not a million. It's going to be a bigger number than a million.

And it just kind of went from there. But it was really for me to start that movement, that industry, that way of financing real estate. It involved a lot of salesmanship and communication and a tireless amount. Right. And a lot of skepticism, a lot of resistance. I had to convince insurance companies, the same people who were insurance company kind of lenders, that viewed this as a threat to their jobs. I had to somehow overcome that to make.

[00:17:31] Speaker A: Somebody had to buy.

[00:17:31] Speaker B: Make them buyers, right? I had to make them buyers.

And the other bond buyers who had never bought real estate risk, didn't understand real estate risk and knew that people were literally dying on the vine with real estate risk. I had to persuade them to consider. So there was a lot of salesmanship involved, a lot of energy expended. And when people would meet me, because I was in my early thirty s at the time, they would frequently express shock, like how young I was, and I would tell them, listen, yeah, I'm young, but if I wasn't this young and didn't have this youthful energy, I don't know that I could do this, because it was a massive amount of energy and tireless salesmanship involved.

[00:18:13] Speaker A: How did you know? You. I mean, obviously that conversation was interesting, but you just had this vision that it could happen, that this industry could come about.

[00:18:22] Speaker B: Yeah, it seemed obvious to me. I knew that I understood the way bond buyers think, which is a relative value based thinking, and that's how I sold it. I would say, okay, listen, if a single, a corporate bond is trading at, whatever, 100 over treasuries, I know there's some level that a single, a real estate backed bond will trade. Maybe it's not 100, maybe it's 200. Maybe it's 300. Tell me the number. And the good news was that the real estate borrower had no other options. So whatever rate I had to charge them in order to placate the bond buyer, they were hugging and kissing me because their alternative was to lose the property. So it didn't matter. They were rate insensitive in that particular moment.

[00:19:11] Speaker A: So that was the best time to make money in that industry once you got up and running.

[00:19:16] Speaker B: Yes. And I'll tell you something, though, it taught me so much, being there, doing that and doing it in an aware state. So, as you suggest, it was the best time because there was no competition. I could charge the borrower anything I wanted and they would be happy. I could tell them whatever the loan value attachment point, and they would be happy. And the bond buyers were getting essentially bribed to take the bonds and getting overpaid for the risk, and they were happy. And we were making, even literally, Milken's.

[00:19:56] Speaker A: Junk bonds probably didn't trade.

[00:19:58] Speaker B: No. We were making fortunes in this process. Fortunes and making very safe loans at exorbitant rates. And what was interesting was that first year or two, everyone saw what we were doing and thought that we were going to blow up. And I never in my life took less risk, not before and not since, like, for me. But it reinforced to me this herd like thinking, and I write about that in my book, that to be great. And I felt that we were great. We were great at what we did, and we brought great value to the world of real estate and to the bond buying world. We brought incredible unique value that lasts to this day, 25 or 30 years later.

And I think to be great, you must be willing to operate outside of the herd, and that's very hard to do, but we did it. And I'm very proud of what we accomplished.

[00:20:59] Speaker A: So at the same time, I was a mortgage banker, and I was told that I had to go on straight commission in 1990, and I was completely out. And then in 92, we came back and I was bought by leg Mason. I want to work for them.

The industry was slow to come back. The first cnbs loan I did, the spread was 360, I think, over the tenure.

[00:21:25] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:21:26] Speaker A: And it was like life companies were, once they were back in, were in the twos at that time.

[00:21:31] Speaker B: Right.

[00:21:32] Speaker A: It's like, well, but look at the property type. I mean, look at where it is. What else is going to trade? It's not going to be a life company deal.

[00:21:39] Speaker B: Right.

[00:21:40] Speaker A: And so it was interesting, but you guys had in the mortgage banking business, it was like a tidal wave that came on that we never expect. It was like, from nothing to this massive amount of capital that just came suddenly out of. From Wall street into the market.

[00:21:56] Speaker B: Well, really, we built a bridge so that the bond market can bring their money over the bridge and express it into real estate. And real estate has never been the same since. And I think that's incredible. Look, let's say there's x dollars of money chasing something. It doesn't matter what it is. It could be biding for your blazer. X dollars of money might be interested in your blazer. If through some innovation, I'm able to bring ten x or even two x money to bid for your blazer, your blazer just got more valuable. And so people have said to me, and I guess I hadn't thought about it in that moment, but no one, probably beside me, has had as big an impact on real estate values because I brought in this new pool of money that had a huge thing. It stayed and it stayed in real estate. And so the permanent impact to cap rates or real estate valuations turned out to be quite profound. I wasn't thinking about that at the time. I was thinking about, there's a huge problem that needs to be solved, and I am attracted to that. I'm attracted to voids. There was a void, and I thought I could solve for this void.

[00:23:11] Speaker A: Before we go beyond that, I want to go way back now to your origin story. Okay, so we'll shift to your origin story. Your book, greatness is a choice, discusses several details about your childhood in Yonkers, New York.

[00:23:23] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:23:24] Speaker A: And your family growing up poor, as you referenced. Talk about a bit about your parents. As you said, they were not good role models, yet you said you learned quite a bit from them.

[00:23:35] Speaker B: Yeah. Well, look, I think that parenting, perhaps only rivaled by marriage, is something that we are literally blind and trying to figure it out on the fly. So I really don't condemn my parents for not necessarily being the best parents. My father was particularly inept at that.

I don't fault him for that. What'd your dad do? My dad was a rabbi.

[00:24:06] Speaker A: Oh, really?

[00:24:07] Speaker B: And he was really good at giving advice, but he's one of those people who were not necessarily good at walking the walk in his own personal life and everyone's life's complex. My dad's life was certainly complex. And he came here as a one year old in 1922 from Poland, now the Ukraine, with his parents who didn't speak the language. The hardships that I think my ancestors. And I write about this in the book that my ancestors and everyone has an ancestor hardship story. You know what I mean? At some point, even for the people who can trace their ancestors to the Mayflower, probably coming here on the Mayflower was no easy journey. And when they got here, life wasn't.

[00:24:53] Speaker C: Easy for them, either.

[00:24:54] Speaker B: So I think everyone has a hardship ancestry story, and I do, too. And for me, it's not that far removed. Right. My grandparents had that story. My father and my mother were the children of immigrants who came here and really struggled. And I compare it, maybe I'll diverge a little bit to today's immigrant situation.

And I would say there's a very big difference in their story and perhaps my childhood and maybe your childhood story in that my grandparents and my parents, too, they didn't come here thinking that this country owed them a damn thing, okay? They came here to leave a place where they felt they didn't have a great future for a place where they knew that they could have a fresh start, and they knew it would be hard. And I think my grandparents never once imagined that the day would involve any fun at all. Like, the word fun wasn't part of their vocabulary. They just worked, and they raised their kids, and they made every sacrifice. Their life was all about hardworking sacrifice.

And I think their joy was serving their children and their grandchildren. I know that my grandmothers, in particular, my grandfathers, both died when I was young, but my grandmothers, the joy that they felt in kind of caring for me and being a grandmother, and believe me, they worked. It wasn't like they were.

They were there for me, which was incredible. And I dedicated my book to a couple of people, including one of my grandmothers, because I've never seen such selfless giving in my life than her and one other woman that I dedicated the book to. But I kind of grew up in that background, and I say the word poor. I did use the word poor, and I use the word poor in an economic sense, but I'm not an economic being, which sounds strange because I'm a wall street guy by background, but I'm not an economic being. I didn't write a Wall street book, and I didn't write a finance book. I wrote a book about life and living and the observations I've had as a person who's lived a pretty interesting walkabout or journey in life.

My parents were poor. I grew up with my mother because my parents were divorced when I was eight. And I don't think my mother had a week of savings, meaning if she didn't work that week, we were like one of the majority of Americans today who had no savings and had the pressure to make the money that week, to pay the bills, the grocery bills, the rent, whatever. And somehow we made it. And I grew up in a neighborhood filled with people like that. And I think that I love that. I treasure that. I'm proud of that, although I wasn't at the time. And I talk about that, too, about how, oh, perhaps I wish I was born in a more affluent place to a more affluent family and had that to kind of fall back on. But in reflection and even in the moment, I was proud of my mother. Very proud, and I still am. And when I say she wasn't the perfect mother, I am completely aware of the hardships that she faced every day just to pay the bills and survive as a single woman in the 1960s and 70s, where that was tough. And with two little kids and no help, my father is a different story. He didn't help, okay? But he also had his issues, and I forgave him long ago for feelings that I might have had that were not so powerful.

[00:28:59] Speaker A: So growing up that way was a character builder for you to some extent.

[00:29:01] Speaker B: Incredible character builder. I felt the burden of responsibility that I think a man feels when he has a family.

By the time I was nine, because I was the man of the house, my father was gone. My little brother was a little kid and kind of a delinquent, too. And my mother had no one to turn to but me, and she treated me because she had no one else as an adult. So I was talked to as an adult, as a confidant, as a person to rely upon, not as a nine year old kid from the time I was nine years old.

[00:29:38] Speaker A: Well, we'll get into this a little later, but it sounds like your father, because he was a rabbi, had some influence on you based on some of the things you said in your book, although you said you came back to religion later on, so I want to get into that a little bit later.

[00:29:52] Speaker B: But it's interesting. I'm blessed to have a great education, and I don't mean college, right. I did not have a great college education.

[00:30:02] Speaker A: Where did you go to college?

[00:30:03] Speaker B: I don't remember. No, I do remember.

I didn't really go too much. That's the thing, okay? I went for the tests. I went as little as I could because I didn't see it as any place to derive value. And I worked full time during college. I was a full time student and a full time worker. And I really just wanted to get out of college with the degree so I could have a better job.

But I had an incredible elementary school education and I would say the most intellectually stimulated and the most intellectually challenged I've ever been in my life in any group, peer group, was 7th and 8th grade. Really? They were the smartest people I've ever been in a room with.

We were challenged intellectually far more than I've ever been challenged in my life since.

That says a lot, right?

[00:30:56] Speaker A: Public school?

[00:30:57] Speaker B: No, I went to a parochial school, otherwise known by jewish people as a yeshiva. I spent half the day learning only in Hebrew, except we learned the Talmud in Aramaic, which is the language Jesus sprung. So I was fluent in Hebrew, pretty good in Aramaic, and then I spent the other half the day speaking English and learning English, normal things that people spend their whole day in class, in school, I learn in half the day and I learn all the other stuff the other half the day. And I went to school from till 05:00 p.m. And by the time I got into 9th grade, I was like, I'm done with this.

[00:31:36] Speaker A: Your father's influence?

[00:31:37] Speaker B: No, not really. I mean, yes, maybe, but I think that my mother was also quite scholarly and I think they both wanted me to have that solid education. And I think that that was a big part of eastern european jewish immigrants put such a huge emphasis on education. I think they understood that a good education is the foundation for a well lived life, whether it's making money or not. Sure, education on higher levels does help income, but I think it just helps you live your life with clear thinking. Right. The Tommyutic studies that I had was like probably going to law school and just logical thinking, like just being able to understand and think things through in a logical, clear thinking way. And my book, I think, is a reflection of that way of thinking that was solidified in me in 7th and 8th grade.

[00:32:38] Speaker A: So once you. Bar mitzvah, that was kind of the graduation for that then, right?

[00:32:43] Speaker B: To some extent, that was almost known, actually.

I think that for many young jewish men and women, the bar bhat mitzvah is a very important moment for me.

I don't know, it was less. I wish it was more. I see it for my kids and it's been an amazing experience for them. I'm sad to say that for me it wasn't. It was more of like, it was expected of me, like going to college was expected of me. Getting bar mitzvah was expected of me. It was just like, almost like an obligation.

Certainly it felt like an obligation.

It was just expected of me. There was nothing celebratory for me about that, which is a bummer. And I know, like, I remember my first born son, God, bar mitzvah.

I saw him change. Like, it literally changed him from a spoiled brat to a beautiful young man. Literally in that day. It was incredible. Maybe it wasn't that impactful for me, maybe because I wasn't a spoiled brat going into that.

Maybe because of the burden of responsibility that had been invested in me since I was very young. So maybe I was a man because that's about becoming a man. And maybe I just became a man when the divorce happened at a much younger age.

[00:34:04] Speaker A: So what was your high school experience, or did you have any fun there?

[00:34:10] Speaker B: I liked sports and I played.

[00:34:11] Speaker A: What did you do sports?

[00:34:12] Speaker B: Basketball, baseball, football. I played around, actually, because I had this incredible intellectual foundation. I went to public high school, 10th and 11th, and then I graduated half year early, so I was barely there for twelveth. I never brought a book home, not a single book. I would do the homework during the class while the teacher was teaching. So one day my mother said, are you really going to school? Because I've never seen a book at home. And I literally didn't bring a book home. But I just say it was easy, given what I had been experienced and challenged with in my younger years.

[00:34:49] Speaker A: So somehow all this was in New York, in the Yonkers.

[00:34:53] Speaker B: All in New York, yeah.

[00:34:54] Speaker A: And then somehow you went out to California.

[00:34:57] Speaker B: Well, my dad, when my parents got divorced, my dad moved to.

So. So from the time I was eight years old, I was visiting my dad in San Diego for a few weeks a year. And so I had this California exposure.

And then the song California dreaming by the mamas and papas. Well, we were young at the time when that came out, and I knew what California was because of my dad. And I too would be sitting there in the winters of New York, wistfully, with tears coming down my eyes when I heard California. Why am I here? Why am I not?

[00:35:33] Speaker A: Right? Right.

[00:35:34] Speaker B: So I always liked California, and I understood the appeal of California. And people hear me talk and they say, well, you don't have a New York accent. And I think by the time I was about nine years old, I realized there is a New York accent and then there's a non New York accent in California. And I just decided, I don't need the New York accent. I'll go with the California neutral accent.

[00:35:57] Speaker A: So you started your career in Huntington Beach, California.

[00:35:59] Speaker B: I did. I did. I started a savings loan. It was the bottom of the, bottom of the bottom of the barrel of finance.

[00:36:08] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:36:08] Speaker B: And my pay was accordingly low. And I just grinded.

[00:36:12] Speaker A: Were you a loan officer? To start with?

[00:36:14] Speaker B: I was a loan officer trainee.

[00:36:16] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:36:17] Speaker B: And I learned a million great things that I wasn't aware I was learning in the moment because, you know, too young and perhaps stupid to actually appreciate what I was learning. But by osmosis, I got a much better mba than anyone who went to Harvard. And that year, it was one year.

That foundation serves me to this day. I learned about corporate interactions. I learned about pettiness and corporate politics and jealousy and how it plays out in the corporate world.

I learned about how regulated lenders are impacted by regulation and how that dance between regulators and regulatees occurs and how impactful that is to the industry that they're serving. I learned about what makes a good loan and what makes a bad loan. I learned things that were invaluable and again, serve me to this very day. And I feel like I was so blessed. And I learned also that if you really want to be great at something, you need to know how to do every function of that. Something from the most low level to the high.

It reminds me of a friend of mine. There's a guy, I think everybody here has heard of the company montage hotels, and they have a pendry in Baltimore. That's beautiful.

And the founder of montage is a guy named Alan Fursman, who has become a very good friend of mine. I adore Alan. And Alan is a giant in the hotel industry. And if you go to any montage or Pendry, you feel Alan, Alan is such a great CEO that you feel his care. He cares for people and you feel cared for. When you go to any of his hotels, it has his personal imprint. Alan started out as a doorman, the front doorman at a hotel. That was his first job in the hotel industry. And he's worked his way up from the guy at the front door to being the founder and CEO of a major international hotel company, luxury hotel company.

I think that's been lost, perhaps more so than I've ever seen it, with the advent of technology, right? Technology has created billionaires and deca billionaires and centibillionaires from young men and women who are in their twenty s and didn't pay their dues. And so when we were growing up, we were taught you got to pay your dues. And Alan paid his dues today, no one wants to pay their dues because there's role models that we didn't have. Right. There were no 25 year old, well, there were no billionaires, by the way, when we were growing up. But even the wealthiest people, they were men, mostly men in their sixty s and beyond.

Yeah, I'm not about inherited, but the people who made money, really, they didn't come into it till they were in their 60s, typically, and they had paid a lifetime of dues to get there. And I think that's what we were informed with when we set out in our career. And I actually am happy about that. I'm happy I traversed that journey, and I'm sure you are, too, that your success is the result of a lifetime of kind of grinding and learning along the way. And I think that's an important thing that I've come to understand about life, and hopefully I communicated it well. In my book, the purpose of life is not about winning. And I know so many people who now are so wealthy because of my journey. I've met many, many mega wealthy people, and as they get older and they are facing the end, they realize that the importance they placed upon wealth accumulation was misguided and it's oftentimes too late. I tell a story in my book of someone that I won't mention his name, and I didn't in the book because I don't want to hurt anybody. But he's a man known well in our industry, who is a friend and who is one such man. He's mega wealthy, and I know him now, and he's quite older, and he's very sad about how he chose to invest his time, his precious time, that it's so fleeting. And he gained massive wealth and massive admiration for his wealth and power that comes with that, but at the expense of experiencing love and other joys that he traded off for that.

So what is it that we're here for? Why are we on earth, right? And I don't think it's for, like, it goes so much against you. Remember when we were young, too, Vince Lombardi was like a role model, even though we were both very young when he was in his career coaching the packers. But he was the most famous coach ever to his time, and he was famous for having said, winning isn't everything, it's the only thing. And that was his mantra. And everyone just hears that and repeats it and thinks, oh, that's great. I've come to think that's so wrong headed. So wrong headed. And it sends people down the path of my friend, who in his 80s chased that whole idea of Vince Lombardi won and ended up with nothing on.

[00:42:15] Speaker A: The definition of winning.

[00:42:16] Speaker B: Well, there you go. But I think we tend to think of winning different definition as the competition, whatever the competition is, whether it's the work competition for money accumulation or the football competition for winning the Super Bowl, I think that the winner in life has experienced a lot of learning and growth along the way in his or her journey. And I think it's all about that. I think it's all about we all have our journey, and it's unique to us, and we're here to learn and grow. And I think that when we see it that way, everyone is a winner.

[00:42:51] Speaker A: It's the name of my community, the iconic journey crest.

[00:42:57] Speaker B: Choice of words from a wise man.

[00:43:01] Speaker A: So, since we discussed your career from there through your pinnacle at Numira recently, what happened when long term capital management collapsed and the russian debt crises hit 1998. Talk about that dramatic impact on your business and why you left Namira and how you weathered through that.

[00:43:22] Speaker B: Well, they're not exactly related, although.

[00:43:30] Speaker C: The.

[00:43:31] Speaker B: Long term capital management collapse and the collapse of my business at Nomura were both attributable to the same russian bond default. So nobody imagined that a country would default other than Argentina, which everyone knows, defaults on their bonds regularly. No one imagined that Russia would default on its bonds obligation. Meaning, tell everyone that had loaned the money, tough noogies, we're not paying you back. Okay, just in layman's terms, what a bond default is.

And that sent the global financial markets into a state of panic.

And people all wanted to, because people act in herd like ways we know and plays out in financial markets all the time. So everyone reacted to the russian. The russian announcement that they were not going to repay their bond obligations. Everyone reacted as though the world that nobody would pay their bond obligations. Nobody. So they started.

The only bond that they felt safe to own was us treasuries. And so they all sold everything except us treasuries. And then they sold whatever bonds they had and bought us treasuries. And so the spread in yield yields on us treasuries collapsed because everyone wanted to buy them. So their price went up and their yield went down, and yields on everything else went sky high, and their prices collapsed.

Well, everyone on Wall street that traded credit, whether it was mortgage backed securities, commercial mortgage backed securities, corporate bonds, anything at the time, they were hedged by shorting treasuries.

[00:45:26] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:45:26] Speaker B: So if you worked on Wall street and you ran a credit business, as we did, you were long mortgages and short treasuries. That was the wrong position for that day. Okay. And so your mark to market losses were growing and growing larger by the day as that herd chased the opposite of that position. Right.

I was already gone.

So I had already left Nomora when this happened, although I had agreed it was all secret, I had agreed to stay on because we had our big soiree that September. The russian bond default happened in July of 1998. I had already left about a week or two before.

[00:46:16] Speaker A: Had you seen the winds?

[00:46:17] Speaker B: Nobody knew. Nobody knew. But I knew that we were in a vulnerable spot if something like that were to happen. But I didn't have a chance to address that risk. I had some ideas, actually, but I left. And I'll tell you the circumstances under which I left, they were not pleasant, but I agreed to stay on and I agreed to stay on the board of directors. And I continued to own a significant stake in the company. So its collapse was very painful for me because I owned a significant stake even after me leaving. That turned out to be worth very little. Now, the reason it turned out to be very little.

No other firm on Wall street took any losses with the exception of long term credit and no mora. And the reason was because everybody else who had the same book, long mortgages or corporates and short treasuries, they just stayed the course. They didn't sell anything. And they knew that in time the panic would reverse itself, as all panics do. And by the first quarter of the next year, by roughly December, January, February of 98, 99, the whole trade reversed itself. And so spreads went back to normal. And if you didn't sell anything, you were fine. You didn't lock in any losses, and your paper losses ultimately were reversed. Nomura sold, and that was done. Long term capital was forced to sell because they were over leveraged.

[00:47:52] Speaker A: They were 99%.

[00:47:53] Speaker B: They were forced to sell.

[00:47:54] Speaker C: Right.

[00:47:56] Speaker B: But the other firms, first Boston, Solomon Lehman, they had as big or bigger losses on a mark to market basis that Nomura did. They just didn't sell. Now, why did Nomura sell? Nomura sold because I was gone and they didn't have faith in anybody there. And so they didn't understand the business and they didn't understand the impermanence of that mark to market loss, and they panicked. As we have seen in the financial markets, foreign investors, like Japanese do when they don't really understand what's going on, and they panic.

Many people I know made a fortune buying from the Japanese.

[00:48:38] Speaker A: Do you think you could have convinced them not?

[00:48:39] Speaker B: They would never have sold. If I was there now, why wasn't I there? So that's the other.

I had a guy that hired me at Nomora.

I left Morgan Stanley, as I told you, to start pursuing this commercial real estate business, which later became known as cmBs. I was backed by Cargill and I had my own little company. And we did, I don't know, maybe a billion dollars worth of business. It was the first billion dollars of cmbs ever done. It wasn't called cmBs. We didn't name it then. And then someone introduced me to someone at Nomora, this particular individual who had been brought in with Max Chapman to kind of turn Nomora into a successful us operation who was obviously very big in Japan, had been in the US for 70 years with some operation that had never once made money. They had never made money in 70 years. And they brought kind of a Wall street legendary figure, Max Chapman, who was CEO of Kidder Peabody, to come run their us business. And he brought one of his right hand guys to run fixed income. That guy met me and he and I got along and he saw what I was doing and he gave me the capital to build my business. So it really wasn't Nomura. It was a brand new business with a financial backing of Nomora by virtue of this one individual who worked for Max.

Well, this one individual who worked for Max when I got there was running fixed income and maybe making a million or two a year.

But he had a percentage deal with no more. So he had a percentage of profits of every business that reported to him.

Well, by virtue of my business reporting to him, he went from making a million a year to about 20 million a year. So he was very happy because I was his golden goose, right? He deserved it. He found me. He believed in me. He kind of paved the way so I didn't have to run into any internal obstacle. Yeah, to build my business and to run my business.

Well, by 1997, we were too big for Nomura, and we needed to have our own corporate identity. We needed to have other investors, other lenders. We were dependent entirely upon Nomora for our financial backing, and we had outgrown them. They were now not doing as well in Japan. We were growing by leaps and bounds and growing internationally. And we deserved and needed our own corporate identity. And we were in the process of doing a spinoff. It's a longer story, it's a whole podcast story and maybe a whole NBA class story. But to kind of cut to basically the bottom line, this individual who hired me felt unthreatened by and unhappy about me leaving, even though I brought him with me in the spin off and was envious of the economic division of the to be formed new company and went to the Japanese and got permission to fire me, even though we were very good friends and I had two right hand guys and he needed one of them to agree to stay on and run the company. If he did fire me, that Boyd fellows, I won't name any names, but one of the two agreed to do that. Okay. One of the two said he would not do that.

[00:52:20] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:52:20] Speaker B: And I don't want to shame anyone or anything.

I could write one of those books, by the way, which would be really painful for people to read. I'll never do that. But faced with that and being a 30 something year old, cocky, borderline arrogant God of Wall street with a lot of money, I didn't react positively or calmly to that news. I felt betrayed. I was betrayed. I never once looked in the mirror and asked myself, how did I let this happen? And maybe how did I help bring it about? What did I do to inspire people to act in this way? I know that now. I know relationships are give and take, but in that moment, I saw evil and I saw good. I saw myself as good and them as evil, and I saw myself as larger than life and someone who didn't need them or anyone. And I basically just said, screw you.

Take the job and shove it. Take the company and shove it up your ass. I'm going to go recreate this without you. And I'm still going to own part of this, which I had a contract to do.

And I think it's similar to Steve Jobs thinking, I created Apple.

Screw you. Remember, they fired him. I'll go create Apple again. Well, he didn't do so. He tried. Next. It didn't work so well. Didn't work so well. And he ended up going back to being CEO of Apple. And that worked out quite well. I had a similar experience. Next. Didn't work out so well for me know.

And we were both a little bit too full of ourselves, perhaps Steve Jobs and me. And not to compare myself to Steve Jobs, but I guess I was that in our industry at that time, and you live and learned. I mean, it's part of, like I say, learning and growing. I'm a different version of myself, thank God, than I was when I was in my late thirty s. And if I wasn't, I would have say I wasted the last 25 years of my life learning nothing.

That was a great learning experience in the moment. I didn't understand how great of a learning experience was. I just felt betrayed and hurt and felt like the rug of my life had been pulled out from under me and lost about what that meant for my future. And I couldn't retell this story that I'm retelling you in short form without tears welling up in my eyes because I was filled with self pity.

And I ended up figuring out, with some help, that I stumbled upon how debilitating self pity and victim mentality thinking is. And I was able to and coached to rethink that story and all stories where one feels victimized and rethink the story from the perspective of the active player instead of the passive player. Okay, I got hit by a bus, but why did I walk out into the street without looking? You know what I mean? It's that kind of thing. And you can cry, you get hit by a bus and you go, man. And the bus driver was texting and you go, well, that's a bad guy. He was texting, driving a bus. I got hit by him. But I also walked into the middle of the street and allowed myself to get hit by the bus. I wasn't a completely passive player.

[00:55:44] Speaker A: You never saw any of this coming?

[00:55:46] Speaker B: No. I was just like that person who walked into the street who got hit by a bus, by a texting bus driver. And it doesn't relieve the burden of responsibility from the texting bus driver when you think that way. But as you own your life and you own your bad stories and your painful stories, you can grow from that. You can't grow if it's always somebody else's fault.

[00:56:11] Speaker C: That's right.

[00:56:12] Speaker B: And you can't grow past it and become a productive human being.

So I thank God that I was able to grow past that victim thinking, grow past that and tell that story in a different way. I really am lucky that I met my second wife and been a great foundation for me in my life and built a great new family, but also helped me prioritize life and what life means and what needs to be prioritized. And I think it was the greatest blessing that I was knocked off of my perch, so to speak, because if I wasn't knocked off, I would never have left. You're intoxicated by the position that you're in when you're in those kind of positions. And I'm sure I was, too. And I've developed into a person I'm proud to be. And I think the person that I was and was heading to become.

Forget about even being proud of.

I wouldn't have enjoyed my own life to the level that I have been blessed to enjoy it.

[00:57:22] Speaker A: So did you have to go through therapy or what did you do?

[00:57:25] Speaker B: No, I mean, not really. Actually, my sister in law, one of my sisters in law told me about a seminar that she went to. It was in LA, oddly enough. And I had a house or an apartment in LA at the time and she didn't know my background, so she wasn't telling me to go because she thought it would be good for me because of my background. She just thought it was great she had gone. And she said, you would love this, not knowing my background at all. And I was like, okay, I'll go because I have one of my philosophies is always go. If someone asks me to go, I believe that that's my destiny to go. I don't believe in coincidences. Right. And so if you're invited somewhere, there's a purposefulness to it, just like there's a purposefulness to everything. So I almost always go. And so I followed my own advice and she said, you would love it. And I said, well, it can't hurt to go and if it stinks, I'll leave. I don't have to spend the whole weekend. It was a weekend thing starting Friday morning.

I figured, can't hurt to go and if I don't like it, I'll leave. And I learned this lesson, this very important lesson about victimhood and victim mentality thinking. And man, we could just look around the world today and blame so much of what is wrong in the world today by collective victim mentality thinking. That would be reversed immediately if they were able to understand what I was taught that day in that seminar.

So it liberated me to live my life in a productive way.

[00:59:04] Speaker A: So that was 1998.

[00:59:06] Speaker B: Well, that seminar was 2000. It took me two years of tears and self pity before I stumbled upon that seminar.

[00:59:15] Speaker A: And then eight years later you joined Cb. So what happened in that interim time?

[00:59:21] Speaker B: Well, I met my second wife and my whole life changed. She's a very powerful woman and she's got a lot of amazing qualities. She opened my eyes to a different way of living life and prioritizing different things, family, health, fun and not work. And at the same time.

So I wasn't really ready to go back to work.

Mentally, I wasn't ready. I wasn't in a position after being betrayed where I felt I can trust people. And if you don't trust people, how do you work? Right? And so I had been betrayed by people I trusted. So I needed to reimagine life and regain my trust in humanity. And I need to get away a little bit. I had led such a big life, and I had so many people in my life. Like Michael Milken once said to me, we became friendly in my no more years. And he said to me, if you're dispensing capital, you'll never be lonely. And I wasn't know I had a lot of friends, right? I was dispensing capital, and I felt I needed to get away from everyone, disconnect from everyone, and see who was still my friend. Perhaps years know I'll resurface years later. And the best place to kind of do that is the big island of Hawaii. There was literally nobody there, and it's very far from everywhere. And so we moved to Hawaii. We spent about three years living on the big island. My wife, myself, we had a young daughter who was one at the time, and we enjoyed life. And it was beautiful. Three years. And it allowed me to clear my head. It allowed me to rebuild myself in a new way. And then I kind of got itchy to come back to work and be a producer again because that's so much of a part of who I am.

[01:01:20] Speaker A: Keep your Wall Street Journal subscription when you were there.

[01:01:22] Speaker B: Well, I pay attention. I definitely pay attention.

[01:01:25] Speaker A: Okay.

[01:01:26] Speaker B: So I came back to the world of work and production in 2006, and.

[01:01:39] Speaker C: It was obviously.

[01:01:42] Speaker B: Bull market. Like a crazy market that made no sense. I hate bull markets. So there was nothing there for me, because in a bull market, no one's paying anyone to be smart. In fact, being Smart is an obstacle to maxing out your return, because smart people see risk, and less smart people don't see risk. So their enthusiasm to buy is not impeded by any fear. And in a bull market, you're rewarded for buying more, not less. Right?

I think bull markets tend to reward people who are a little less skilled or perhaps less ethical. Both. They just buy unimpeded by any concern for risk. That's not me.

I'm not either of those people.

[01:02:36] Speaker A: I could see something happening when I was in the real estate, I was working for Acmans. If at the time, I was in New York at the real estate board of whatever, the real estate board of New York meeting, and I was sitting there and watching a guy from, he was with either Bear Stearns or cs first Boston, and he was drawing this chart of cmBs, and he said, let's now tranche the a piece. So we tranched the a piece. I said, wait a minute, you're tranching the a piece and you're trying to sell the c position of the a piece as if it's, I mean, I said, wait a minute, there's too much math here.

[01:03:14] Speaker B: Well, the lemon was dry, and they were trying to squeeze another drop or two out of the lemon, but it was dry. Yeah. And they were doing everything they can to find another drop out of that laminate, everything. So in the problems, obviously, cmbs went awry.

Asset values were incredibly wrong because fueled by too much debt that was poorly priced, incorrectly priced. But the root of the problem was in the single family mortgage market, which I came from and I understood as well as I understand the commercial market and on the single family side, both because of public policy and also because of Wall Street's desire to squeeze more drops out of a lemon, that the lemon has.

Literally hundreds of billions of dollars of loans were being extended to borrowers who had no ability to ever repay the loan. None.

So how could that end? And when people say, well, securitization is a problem, it's like, no, if you have a sausage factory and you put beautiful, healthy meat, grass fed from animals that have been treated very humanely, into the sausage machine, you're going to have delicious and healthy sausages coming out the other side. On the other hand, if you put crappy meat from poorly treated animals into the sausage factory, the other side will produce very unhealthy sausages. Securitization is just the sausage factory. You put good loans in, you're going to get good bonds. You put bad loans in, you're going to get bad bonds. It's pretty simple. Securitization created that calamity, as much as food, creates obesity. Food doesn't create obesity. It's what you do with the food that creates obesity. And if you're eating good food and the right amount, you're going to be just fine.

So I hear a lot of times. Are you personally, do you feel responsible for 2008? Not at all. I didn't make any bad loans. I didn't create a machine that kind of encouraged people to make bad loans. The system made bad loans.

[01:05:26] Speaker A: So you started your enterprise at CBRE in that year?

[01:05:31] Speaker B: I did, because I knew the world was going to fall apart. And I am attracted to those moments. Those are moments where smart, disciplined people are rewarded, where there is a differentiation. And I like those moments. And I like figuring things out. I like solving problems. I like all that stuff and I knew in 2007 that there would be historic problems coming from the excesses of 2005 and six. And I was right. And so I was attracted to come back to work. I did end up at CBRE. I was friends and am friends with Bret White, who was the CEO of the firm.

Bret and I had no plans for me to go to work at CBRE. And we just went to go play golf the week of Christmas 2007. And he asked me, it was me and him and two other guys. And he called me and he said, could you come and just have lunch with me before the other guys come? Because I don't understand what's going on in the world. And you're my smartest financial friend, and I would like for you to explain it to me. And so I met him for lunch. I explained him what I thought was going on. I explained to him how there would be losers and how CBRE could respond in a way that might be capitalized upon that. And he asked me if I would ever consider coming to work at CBRE. And I told him, no. There's 35,000 people, public company. That's not really appealing to me. I'm an entrepreneurial guy. And he said, I said to him, but I guess you're the CEO. So if you could create an entrepreneurial island for me with an entrepreneurial deal that allowed me to own part of my business, I suppose I could use this platform in extremely productive ways. And so he said, okay, let's do that. And then I did ultimately join CBRE. I had a wonderful time there.

[01:07:30] Speaker A: I mean, CBRE is brokers, right? Brokers are independent people.

[01:07:34] Speaker B: CBRE is an amazing company. It is, as you know, amazing company.

I loved my time there. I thought the people were first class through and through.

I was so impressed with the company. And I still to this day, am deeply impressed with the company.

[01:07:51] Speaker A: So you were there for how long? How long was it?

[01:07:54] Speaker B: I was there for four or five years. There was a management change. As you know, Bret left.

Brett was my rabbi. Bret had created that entrepreneurial island for me. And even though I had legal documentation for my deal with CBRE, let's just say the successor management team wasn't happy with that because I was an outlier. Like, I was the only person in the history of CBRE who owned part of their business. They didn't like that exception to the rule.

They made me an offer that I could only refuse, and I did.

[01:08:30] Speaker C: Okay.

[01:08:31] Speaker B: So that's ultimately what left me to leave again. I don't necessarily blame them. I mean, I think that when you're running a big company, it's hard to have exceptions to rules. And I get a public company. I get it. I don't have any bad feelings. Bob Solentic, who wasn't necessarily directly involved, is a CEO, and we're very good friends. I have lunch with him a couple times a year. I really care for him as a person. He's been in my house. I have nothing against anyone. I think he made. And people made decisions with regards to me that they felt they had to make for the betterment of the company, and that was their job, to make those.

[01:09:12] Speaker A: Were you making contrarian bets when you were?

[01:09:14] Speaker B: Not at all. No, not at all. I was operating as I was supposed to, and I was running what was the most profitable part of the CBRE investors business.

I was building a great business and delivering returns that were at or higher than we promised investors and growing the business. Well, I did my part. I think that the deal, the entrepreneur's deal that I cut, didn't sit well with them.

[01:09:39] Speaker A: Got it.

[01:09:39] Speaker B: And that's okay.

[01:09:40] Speaker A: Understood. And then subsequently you formed a company.

[01:09:44] Speaker B: Yeah, I decided to be a real entrepreneur instead of being an entrepreneur in an island of a big company.

And that has been what I've been doing for the last, I guess, eight years or so. And we had a bunch of different pockets of money, separate accounts, primarily. But we had one large commingled fund. And the large commingled fund, I kind of dodged a bullet for myself and my investors in the sense that I saw that when Covid came in 2020, I felt that the world was entering a new risky period, that I didn't know how that risk would manifest itself negatively. I just knew that it would likely manifest itself negatively. I would never have imagined that the Fed would march interest rates up as they have. I think it's, by the way, incredibly stupid and destructive, unnecessarily destructive, but they did it. But I knew that something negative was likely to happen in the financial markets because of inspired by Covid. And that caused me to think, I want to get my investors liquidity because we were in illiquid positions. And so I spent the next 18 months, I shut the fund. It was an open ended fund, and I pursued liquidity. And I was able to consummate a merger with a publicly traded mortgage REIT that closed fortuitously in March of 2022 with no lockup. So literally, the peak price for mortgage reits, no lockup rates, had not yet begun to be marched up.

We got out at the nick of time. Now, since that time, I've been uncomfortable with the market. I remain uncomfortable with the market. So I haven't launched any new vehicles. And I've been sitting around patiently because we both have been around this industry a long time, 40 years plus. And what we've seen is that when price action happens, that values go down abruptly. There's usually a years long period of nothing happens, because sellers obviously don't want to sell.

Buyers don't want to pay yesterday's prices, they want to pay today's cheaper price.

[01:12:14] Speaker A: Don't trade.

[01:12:15] Speaker B: And until they're forced to, things don't trade. So I knew that was likely to occur, and I didn't want to go raise money, promise investors activity that I didn't think would happen. And it turns out I was right. And so I wrote a book, and instead of managing money, I basically became an author.

[01:12:31] Speaker A: Let's talk about volatility for a minute. Okay, so you pioneered the CMBS business and grew it significantly up to 98. Then a hiccup occurred, and then it recovered in the 2000s, grew astronomically until the GFC in 2008, when it crashed once again, and then once again recovered. Talk about the volatility in this business and compare it with the lower beta life insurance lending business that had more slack and alternative options, allowing for diversification. Do you think CMBS is a sustainable business model, and could it evolve into something less volatile?

[01:13:08] Speaker B: Okay, I think that the notion of volatility is a poorly and misunderstood notion.

[01:13:20] Speaker A: Okay.

[01:13:25] Speaker B: For those who are not seeing this, I'm holding up my iPhone. So if this iPhone in my hand today could fetch $100, I'm just picking a number, $100.

And then tomorrow, there was a flood of this vintage iPhones hit the market. It would not be worth $100 anymore. It'd be worth something less and maybe substantially less than $100. Right?

And if I was forced to sell this iPhone, I would find out exactly what the price that it would fetch, and I would go, man, the price of iPhones are very volatile. It was $100 yesterday, and now maybe $35 today. But if I didn't have to sell, and I just thought, well, people are paying a lot less. There's a lot more iPhones for sale. I just put in my pocket. I'm going to use it for another year and maybe two. Don't tell me what it's worth. I don't even care. It's not information I'm interested in. I wanted $100. There's not $100 bid. I don't need to know.

So then, I don't know how volatile it is. I just know it's a little less than $100, but my price, $100, and there's no $100 bid. I think that the real estate industry. So Sam Zell, I would give him, and I would give.

There was a guy at Merrill lynch who ran equity investment banking, real estate equity investment bank. Richard Salzman.

Richard Salzman was the Ethan penner of Reits. And Sam Zell really was Richard's kind of like, horse that he rode to the success of creating today's mortgage real estate REIT industry, or the REIT.

I created the debt side of that. What we both did was we brought real estate out of the closets and out of the conference rooms into the public market. And so now the public market was setting a price every minute for real estate, and that price was moving based on the public market's willingness to pay for real estate debt or real estate equity. And it was moving every minute before that. Before 1990, roughly 92 or 93, all of real estate was private, all of it. So the loans that were made by insurance companies or banks never saw the light of day. They were made and owned by that lender.

Documents were sitting in a drawer, and when the loan matured, if the borrower couldn't repay it, then there was just a negotiation of an extension. Pay me a fee and we'll talk about it in a year or two. Right. And the same thing with real estate assets. There was no price discovery. And now, all of a sudden, with the advent of the REIT and the cmBs, there was price discovery. So when we look at CMBs or REITs, we see price volatility, because we have minute to minute, day to day market opinion of the value of those things.

The real estate that is not in the public market, there's no opinion being expressed about its value minute to minute or day to day. But it's fairly safe to say that if that real estate were to be pulled out, if that loan was pulled out of the insurance company's drawer and sent out into the public market for price discovery, they would discover it's just as volatile as cmBs, you understand?

[01:17:13] Speaker A: Well, because the markets are that way today. But when I grew up in the business and I started a prudential.

[01:17:18] Speaker B: Yeah, but because there was no public.

[01:17:20] Speaker A: No, we didn't have that. We didn't have trading mentality.

[01:17:23] Speaker B: Well, there was no connectivity between the capital markets and real estate assets of any kind. I agree. No connectivity.

[01:17:31] Speaker A: Real estate was looked at as.

[01:17:32] Speaker B: But real estate was volatile.

It's just that you didn't know it.

[01:17:38] Speaker A: Well, that's true, because it didn't trade as much.

[01:17:40] Speaker B: Well, there was no reason. It was a longer term, but there was no vehicle for trading. And so you sold when you were in the money and you didn't sell when you weren't in the money, and that was that.

[01:17:53] Speaker A: It's interesting, though. I grew up in appraising property, and I was in the appraisal institute looking at long term value. And how did you come up with a cap rate? We had what was called the band of investment. You looked at what's the equity return you need? What's the debt return? So this was a scientific structure at that time. We didn't have Wall street to trade off, except inside the insurance companies. They were trading bonds, but they disconnected.

[01:18:19] Speaker B: Real estate from that thing.

[01:18:21] Speaker A: Well, they had to allocate their portfolios.

[01:18:23] Speaker B: But they disconnected mortgages, but they disconnected, just like I think in venture capital is another place where they've done a very good job of disconnecting reality, as though there's something called gravity. But gravity doesn't apply to this area.

I think it's just self deceit.

Well, people live very happily in self deceit.

[01:18:45] Speaker A: They like to tell you, life insurance companies will tell you, they allocate their assets accordingly based on risk, as their perception was at the time.

[01:18:53] Speaker B: And I'm sure they were, but I think they were misunderstanding the risk of the real estate market. They're probably because there was no reminder.

No, they didn't mark the market without the reminder. They don't know how risky it is.

[01:19:06] Speaker A: No mark to market.

[01:19:07] Speaker B: There's no reminder.

[01:19:09] Speaker A: Yeah, I agree. I can argue with that.

[01:19:11] Speaker B: By the way, I'm going to tell you a story.

[01:19:13] Speaker A: Okay.

[01:19:13] Speaker B: It inspired me to abandon my initial inclination to create cmbs. So my initial inclination was in 1988, not 1993. And in 1988, I was a young big shot at Morgan Stanley, trainer, running the credit risk mortgage business at Morgan Stanley. And I thought, why not go after that big giant market that no one seems to be after on Wall street called commercial real estate? So I started to dip my toe into that arena. And if you remember, Morgan Stanley owned a real estate brokerage company. No, there was another one, and I'm blanking on the name, but if I said it, you would. Brooks Harvey. Brooks Harvey. They own Brooks Harvey. So I moseyed over to talk to some of the guys at Brooks Harvey who were as far afield from bond trading desks where I lived, from an intellectual or knowledge based standpoint, as one could imagine. And they were telling me, I said, what's going on in the world of commercial mortgages? And they said, well, it just so happens we're arranging a mortgage right now for this office building in midtown Manhattan. And the lender was travelers Insurance company.

And I said, well, what kind of terms are you getting the borrower? And it was like a ten year loan, and the rate on the loan was lower than the ten year us treasury.

[01:20:46] Speaker A: Lower.

[01:20:47] Speaker B: So think about this. Think about what disconnection means. Some imbecile, the CIO at travelers, is literally lending money to an office building, and all the risks attended with that, when all he had to do is buy the US ten year treasury and he'd have a better yield.

And I thought, okay, there's no cmbs here. And I went back to the residential, forget this, this is insanity, because the disconnection created those kinds of, kind of.

[01:21:21] Speaker A: Like, mortgage bankers love that pricing.

[01:21:23] Speaker B: Of course, it made great sense to you as an intermediary, but as an investor, it made less than no sense as the world changed and the real estate market got exposed to the capital markets and relative value, which goes back to what we talked about at the beginning of this conversation, was now introduced to the real estate investment world. The world's never been the same for real estate, but they still do talk about, gee, CMBS is volatile, but how come my loan portfolio is not? And the reason is price discovery. You don't ask for price discovery. If you did, you'd find out it's very volatile.

[01:22:03] Speaker A: Earlier this year, you were interviewed on another podcast and cited that the largest macro trend over the last 40 years was declining interest rates, and that has now changed. Howard Marks of Oak Tree Capital also made that observation recently and has recommended a reallocation of their investments. Internally. You indicated that you will be looking toward inflation protected investments, and due to the outstanding debt on the US balance sheet, inflation is inevitable.

Perhaps elaborate on this and what strategies you would recommend to young professionals in our industry and in general, about where to place capital today.

[01:22:45] Speaker B: Well, I think there was like three questions embedded in that question, so I'm going to try to address that. That's a good way to ask the question. All right, so I think, first of.

[01:22:54] Speaker C: All.

[01:22:57] Speaker B: I'll start with young people in the real estate industry. I love real estate for a variety of reasons. I love real estate. And as you and I were talking even before we started the podcast, primarily because real estate is a reflection of society's inclinations, right? And so if you want to be a good real estate investor, you must ask and answer the question, in what physical structures do people want to enjoy life?

[01:23:31] Speaker C: Right?

[01:23:32] Speaker B: And if you can answer that question, you're going to invest accordingly and do very well. And if you don't answer that question or even ask that question, you'll be stumbling and bumbling in your career. And I think too few real estate people think that way. So when I write a book on philosophy, which I did, and people think, well, why did a guy who's known in real estate write a book on philosophy? It's because I think philosophy and understanding human nature, human behavior is fundamental to being a good real estate person. And so I would tell young people today, the world is in a state of incredible, as you well know, incredible change. The things that were attractive in John Co. And Ethan Penner's journey in life as young men are very different today. People's desires of how to live life, where to live life, how to allocate their time, how to interact with each other, then where to interact with each other, those are very different than in our lifetime. And most of the real estate stock in the world today was built to answer that question for our lifetime and even generations before us. So that means there's a lot of shaking up that's going to occur in real estate. And shaking up is very rewarding for young, thoughtful, enterprising people. So I think the future of real estate is going to be exciting and very rewarding for people who think philosophically, who are students of human behavior, and could express themselves accordingly in this industry. It's very exciting. I think technology obviously will have a huge impact in answering some of those questions. And so I also talk in my book about intersections and how real estate itself is an intersection business, because it lives at the intersection of a lot of things, politics and zoning, tax policy, construction and design, finance, capital markets and economics, human behavior.

Intersections. I would find intersections, live in intersections. It's fun and rewarding. So that's one. That's the last question you asked. The second question you ask about investing in inflationary places where inflation. I think inflation is one of the most poorly understood ideas in economics.

I think that people often confuse cause and effect when thinking of inflation. So they look at higher interest rates as perhaps even the definition of inflation, or certainly the result of inflation.

Sometimes maybe they think of it as the cause of inflation.

I think of that as somewhat disconnected today. I think that the reason is because the federal government interest rates used in my bond trading years when the Fed had a much less invasive orientation towards the financial markets than they have expressed in the last decade and continue to express. Inflation was the market price for money, right, I'm sorry? Interest rates was the market price for money. So someone wanted to borrow, someone had money to lend, and interest rates was the price of that transaction.

And it was largely a free market. So if there were more people wanting to borrow than wanting to lend, interest rates went up. If more people wanted to lend than to borrow, interest rates went down. Pretty simple.

When 2008 happened and the world as we know it almost ended, the Fed decided that, as the Fed does, when they see worlds teetering on anarchy, that they needed to solve for that anarchic risk. And the only lever they have is to flood the market and the world with cheap dollars. And so they flooded. There's been $8 trillion of essentially new money has expressed itself since 2008 into the world. And that is, by definition, inflation. So if you go back to the economic definition of inflation, when the world word was, because the word inflation has been in the english language for a long time, but it only started to be used, I believe, around the 1920s or 30s in relation to economics. And the word was used to describe the inflation of money supply. That's what it was. So the word inflation originated in economics as a measurement of money supply. Money supply is inflating. Well, that's what happened. $8 trillion was conjured out of thin air and injected into the world by the Fed. That is the definition of inflation. And yet what was interesting is that during that $8 trillion infusion, which was historically large, interest rates remained historically low. And people were going like, well, there's no inflation. Interest rates are 1%.

Yes, there is inflation. $8 trillion was created. It's just that interest rates were being suppressed, and they were being suppressed by the same powerful forces that had created the $8 trillion, which is go back to why I said I was very surprised to see the Fed allow rates. By the way, the word Fed allow is also a weird thing for a free market person like me to say. I grew up on a bond trading desk where the Fed didn't intrude, and so markets determined where rates went. But since 2008, the Fed has determined where interest rates go. The bond market is just there, but it's not really determining much. Supply and demand don't determine much. The Fed determines where rates go. And so I wouldn't make interest rate bets today. I think that interest rates are, if you say, what does the Fed, the US government need? They need interest rates to go back to 1%.

Are they smart enough to know that? I'm not so sure. So I wouldn't make interest rate bets. I do, though, believe inflation is with us. Wherever interest rates go, it doesn't matter. And I think owning inflation protection assets, not owning cash, will continue to prove to be a good idea.

So I think that answers most of your question.